I discovered Stephen King in 1984, when I serendipitously picked up a copy of ‘Salem’s Lot in my high school’s library.

I discovered Stephen King in 1984, when I serendipitously picked up a copy of ‘Salem’s Lot in my high school’s library.

I was immediately hooked. I set out to read everything King had published to that time–which was considerable, even in 1984.

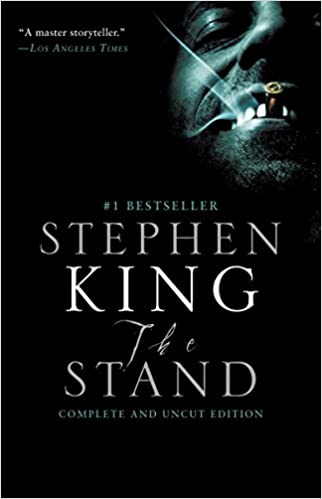

My initial instinct was to focus on King’s novels. I read The Dead Zone and Cujo, The Shining, and (of course) The Stand.

Oh, yes, and Carrie. I liked Carrie a lot.

I was methodically working my way through the King oeuvre. I mostly did this by going through the books on the library shelves. (There was no Wikipedia, no Internet, in 1984, you’ll remember.) After I’d read all of the Stephen King novels I could find, I came across this other book: Night Shift.

Night Shift, I immediately discovered, was not another novel, but a collection of short stories.

I was a bit skeptical–as much as I already loved Stephen King. My experience with short stories thus far had been limited to assigned readings in my high school English class.

I had a teacher that year who was obsessed with Ernest Hemingway. He particularly loved “A Clean, Well Lighted Place”. This is a story in which an old man has a drink in a cafe, and two waiters talk about him. Another Hemingway story, “Hills Like White Elephants”, consists of an oblique conversation about how an unmarried couple will handle an unwanted pregnancy.

Hemingway’s short stories bored me to tears. I couldn’t relate to the old man in the cafe in “A Clean, Well Lighted Place”. I was fifteen, after all. And at that age I hadn’t even had sex for the first time yet, so the roundabout conversation between the man and the woman in “Hills Like White Elephants” left me cold, too.

I’m a bit older now, and I’ve acquired some appreciation for the short stories of Hemingway. (Hemingway really isn’t the best choice for younger readers.) But at that time, my readings of literary short fiction had convinced me that short stories were little more than pretentious vignettes in which nothing much happens.

Nevertheless, I took a chance on Night Shift. I was glad I did.

Night Shift was–and still is–filled with short stories that grab you from the get-go. Stephen King’s forte, I had already discovered, was to transform the ordinary into something dark and magical. The stories in Night Shift accomplished this just as adroitly as King’s novels.

Take, for example, the story “I Know What You Need”. This is a story about a popular young woman named Elizabeth Rogan, who finds herself inexplicably attracted to a social misfit named Ed Hamner, Jr. As the title implies, Ed always seems to know what Elizabeth needs.

But there is a dark secret behind Ed Hamner’s intuition. What is it? I’m certainly not going to ruin “I Know What You Need” by telling you here.

The events in “I Know What You Need” take a supernatural turn, but the initial setup is something that everyone can relate to. You meet a stranger who simultaneously attracts you and arouses your suspicion. Who hasn’t been in that situation?

And then there is “Quitters, Inc.” This tale concerns an agency that uses highly unusual methods to help people stop smoking. There are no ghosts in this one; but King does present a unique spin on bad habits…and how difficult it is for us to give them up.

“Quitters, Inc.”, just like “I Know What You Need”, is immediately accessible. Everyone has struggled with a bad habit of some kind. That might not be smoking, in your case: Maybe it’s gambling, or overspending, or overeating, or watching Internet porn. Unless you’re a very unusual person, you have at least one bad habit. What would it take to get you to quit yours?

One of the best stories in this book is “Jerusalem’s Lot”, which is written in the same fictional universe as King’s novel, Salem’s Lot. Like the novel of a similar name, “Jerusalem’s Lot” has vampires. But these aren’t sissified, teenage girl heartthrob vampires, like you’ll find in Stephanie Meyer’s crime against vampire fiction, Twilight. These are real vampires: dark, evil, and very, very scary.

Some of the stories in Night Shift have been made into movies. I am here to tell you that the movies haven’t been nearly as good as Stephen King’s stories.

To cite just one example: Maximum Overdrive, which hit the theaters in 1986. The only good thing to come out of Maximum Overdrive was the AC/DC song, “Who Made Who”. The film adaptation of “Sometimes They Come Back”, made in 1991, is a little better. But not by much.

Read the stories. Ignore the Hollywood cash-grab film versions.

All of these stories involve matters of life and death (as all great fiction does); but not all of them contain elements of the macabre or the highly unusual. Two stories in particular, “The Woman in the Room”, and “The Last Rung on the Ladder” are stories that “could happen” without violating any of the rules of what we call “the real world”. Nevertheless, these stories involve real elements of suspense; and they both conclude with an emotional gut-punch.

I am a longtime Stephen King fan, but I am not an uncritical one. I haven’t hesitated to pan some of his clunkers. Cell, Lisey’s Story, and that horrid doorstop, Under the Dome, stand out among Stephen King’s turkeys. (Hey, the guy has been professionally writing since Richard Nixon was president; not all of his stuff can be brilliant.)

Even King himself admits that The Tommyknockers and Dreamcatcher leave much to be desired. I personally prefer the “old”(pre-1986, pre-It) Stephen King books to the newer ones. The Outsider (2018) has been on my bedside reading table for months now. The Outsider is a book worth reading, but not one that keeps me compulsively turning the pages.

But Night Shift is that good. These stories were all written when Stephen King was a relatively unknown writer, before he had become a “brand”. King wrote most of them for publication in men’s magazines. To put the matter crudely, these stories had to vie for male attention with photos of nude and scantily clad young women. They therefore had to hook readers from the very first paragraph.

And since they were originally written for magazine publication, not a word could be wasted. Every story in Night Shift is taut and economically written. There is no hint in Night Shift of the bloated literary style that would eventually emerge in the 850-page, indulgently overwritten 11/23/63.

I envy you, in a way, if you are new to Night Shift. I have read these stories so many times, that I now take the events in them for granted. I will always admire these tales, but I can no longer read them with virgin eyes.

But perhaps you can. If you haven’t read Night Shift, then you owe it to yourself to pick up a copy of this book.