How I wrote a horror novel called Revolutionary Ghosts

Or…

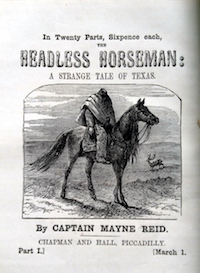

Can an ordinary teenager defeat the Headless Horseman, and a host of other vengeful spirits from America’s revolutionary past?

The big idea

I love history, and I love supernatural horror tales. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” was therefore always one of my favorite short stories. This classic tale by Washington Irving describes how a Hessian artillery officer terrorized the young American republic several decades after his death.

The Hessian was decapitated by a Continental Army cannonball at the Battle of White Plains, New York, on October 28, 1776. According to some historical accounts, a Hessian artillery officer really did meet such an end at the Battle of White Plains. I’ve read several books about warfare in the 1700s and through the Age of Napoleon. Armies in those days obviously did not have access to machine guns, flamethrowers, and the like. But those 18th-century cannons could inflict some horrific forms of death, decapitation among them.

I was first exposed to the “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” via the 1949 Disney film of the same name. The Disney adaptation was already close to 30 years old, but still popular, when I saw it as a kid sometime during the 1970s.

Headless Horsemen from around the world

While doing a bit of research for Revolutionary Ghosts, I discovered that the Headless Horseman is a folklore motif that reappears in various cultures throughout the world.

In Irish folklore, the dullahan or dulachán (“dark man”) is a headless, demonic fairy that rides a horse through the countryside at night. The dullahan carries his head under his arm. When the dullahan stops riding, someone dies.

Scottish folklore includes a tale about a headless horseman named Ewen. Ewen was beheaded when he lost a clan battle at Glen Cainnir on the Isle of Mull. His death prevented him from becoming a chieftain. He roams the hills at night, seeking to reclaim his right to rule.

Finally, in English folklore, there is the 14th century epic poem, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”. After Gawain kills the green knight in living form (by beheading him) the knight lifts his head, rides off, and challenges Gawain to a rematch the following year.

But Revolutionary Ghosts is focused on the Headless Horseman of American lore: the headless horseman who chased Ichabod Crane through the New York countryside in the mid-1790s.

The Headless Horseman isn’t the only historical spirit to stir up trouble in the novel. John André, the executed British spy, makes an appearance, too. (John André was a real historical figure.)

I also created the character of Marie Trumbull, a Loyalist whom the Continental Army sentenced to death for betraying her country’s secrets to the British. But Marie managed to slit her own throat while still in her cell, thereby cheating the hangman. Marie Trumbull was a dark-haired beauty in life. In death, she appears as a desiccated, reanimated corpse. She carries the blade that she used to take her own life, all those years ago.

Oh, and Revolutionary Ghosts also has an army of spectral Hessian soldiers. I had a lot of fun with them!

The Spirit of ’76

Most of the novel is set in the summer of 1976. An Ohio teenager, Steve Wagner, begins to sense that something strange is going on near his home. There are slime-covered hoofprints in the grass. There are unusual sounds on the road at night. People are disappearing.

Steve gradually comes to an awareness of what is going on….But can he convince anyone else, and stop the Headless Horseman, before it’s too late?

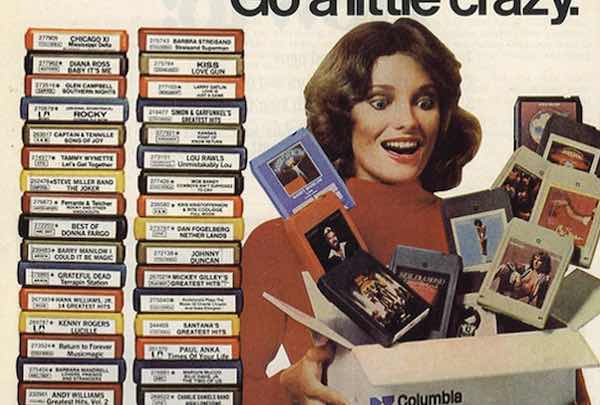

I decided to set the novel in 1976 for a number of reasons. First of all, this was the year of the American Bicentennial. The “Spirit of ’76 was everywhere in 1976. That created an obvious tie-in with the American Revolution.

Nineteen seventy-six was also a year in which Vietnam, Watergate, and the turmoil of the 1960s were all recent memories. The mid-1970s were a time of national anxiety and pessimism (kind of like now). The economy was not good. This was the era of energy crises and stagflation.

Reading the reader reviews of Revolutionary Ghosts, I am flattered to get appreciative remarks from people who were themselves about the same age as the main character in 1976:

“…I am 62 years old now and 1976 being the year I graduated high school, I remember it pretty well. Everything the main character mentions (except the ghostly stuff), I lived through and remember. So that was an added bonus for me.”

“I’m 2 years younger than the main character so I could really relate to almost every thing about him.”

I’m actually a bit younger than the main character. In 1976 I was eight years old. But as regular readers of this blog will know, I’m nostalgic by nature. I haven’t forgotten the 1970s or the 1980s, because I still spend a lot of time in those decades.

If you like the 1970s, you’ll find plenty of nostalgic nuggets in Revolutionary Ghosts, like Bicentennial Quarters, and the McDonald’s Arctic Orange Shakes of 1976.

***

Also, there’s something spooky about the past, just because it is the past. As L.P. Hartley said, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.”

For me, 1976 is a year I can clearly remember. And yet—it is shrouded in a certain haziness. There wasn’t nearly as much technology. Many aspects of daily life were more “primitive” then.

It isn’t at all difficult to believe that during that long-ago summer, the Headless Horseman might have come back from the dead to terrorize the American heartland…