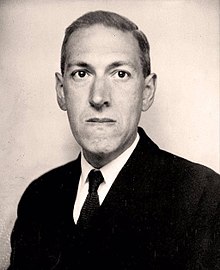

I’ve been working my way through that body of H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction that is loosely based around the Necronomicon, or the Cthulhu Mythos cycle. (Actually, I am listening to the audiobook edition, mostly while I mow my lawn and work out at the gym.) This edition, read by various narrators and published by Blackstone Audio, is the edition authorized by the Lovecraft estate.

The readings are well done. The narrators take Lovecraft’s frequently purple prose seriously, without overdoing it. If you like audiobooks and you like Lovecraft, you’ll enjoy this audio collection.

Lovecraft’s body of work is partly nostalgia for me. I read most of Lovecraft’s stories during my college years. I discovered Lovecraft while browsing through the shelves of the University of Cincinnati bookstore in 1988. Also, Stephen King had mentioned him in several of his essays.

Reimmersing myself in Lovecraft after all these years, a few things stand out, both good and bad.

Let’s start with the good.

First of all, H.P. Lovecraft had an incredible imagination. When he wrote these stories, there were no horror movies. There wasn’t even much fantasy fiction as we know it today. Lovecraft died in 1937, the same year that The Hobbit was published. Yet Lovecraft created so many horror/dark fantasy tropes and conventions from thin air.

Working within the constraints of the pulp fiction era, Lovecraft did a fairly decent job of establishing continuity across his stories. The Cthulhu Mythos cycle isn’t technically a series. These stories were published individually, at different times, in various pulp magazines of the 1920s and 1930s. The marketplace more or less forced Lovecraft into the short story/novella form, and every story had to begin with a blank slate. The writer couldn’t assume that any given reader had read his previous works. Nevertheless, when Lovecraft’s stories are compiled, there is a discernible consistency running through all of them.

And yes, his purple prose. Lovecraft was hyper-literate. You can’t read, or listen to, Lovecraft’s stories without increasing your vocabulary.

Now for the not-so-good.

His narrative style. Lovecraft was a contemporary of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Read Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” or Fitzgerald’s “Winter Dreams”, and you’ll definitely see the differences.

Hemingway and Fitzgerald wrote in a style that we would recognize as modern. Hemingway, in particular, was well-known for his direct, economical prose. But both Hemingway and Fitzgerald thought in terms of showing, rather than telling.

Lovecraft, by contrast, writes more like Herman Melville or Thomas Hardy. Rather than creating scenes on the page, Lovecraft often simply tells you what happened. This makes his writing occasionally cumbersome to wade through, and less accessible to modern readers.

There isn’t much we can say about Lovecraft’s characters, because his characters are paper-thin. They exist only as observers of the supernatural phenomena in his stories.

There are notably few exceptions here. The two main characters in “Herbert West—Reanimator” stuck in my mind a bit longer than the characters in the other stories, who disappeared as soon as the stories were over.

The typical Lovecraft character is a scholarly male recluse who is drawn into arcane research and observations by chance, or by idle curiosity. Lovecraft has virtually no female characters. Not even any damsels in distress.

In some literary genres in recent years, there has been a tendency to depict every female main character as a tough-talking heroine who can whip every male villain she encounters, even if they’re twice her size. We often see this in television shows and movies, and no one believes it.

But Lovecraft errs in the opposite extreme: I don’t want to read female characters that were obviously crafted for the sole purpose of making a feminist statement. But I don’t want to read a fictional world that is entirely comprised of guys who can’t seem to find dates, either.

Lovecraft’s writing also reveals his prejudices, which were extreme and extensive even by the standards of his time. Lovecraft looked down on just about everyone who wasn’t an Anglo-Saxon New England brahmin. His stories are filled with savage Africans and “swarthy”, conniving Greeks and Italians.

Not that he cared much for white, native-born rural people, either. Multiple Lovecraft stories discuss the degraded hill people who live in the backwaters of Vermont, for example.

There has been much writing, and much posturing, in recent years, about “canceling” Lovecraft because of his attitudes on race. His name was removed from a prominent award, and some book bloggers have even declared that Lovecraft’s fiction is no longer suitable for people with the “correct” attitudes on social and political issues. The hand-wringers often forget that while Lovecraft certainly didn’t like African Americans, he didn’t like much of anyone else, either. Lovecraft was an equal-opportunity snob/bigot.

I am not going to make a show of being offended by a piece of pulp fiction that was written eighty or ninety years ago. But an undeniable fact remains: H.P. Lovecraft comes across as a rather narrow-minded person with a narrow range of experiences and interests.

That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t read his fiction. As I said by way of disclaimer: I’ve already read all of these stories at least once. (I believe I’ve read “The Colour Out of Space” four or five times, the first time in 1988.) The scope of Lovecraft’s imagination was so broad, that these stories are worthwhile for any reader drawn to horror, dark fantasy, or so-called “weird fiction”. Lovecraft was a flawed man and a flawed writer; but he nevertheless produced some very engaging tales.