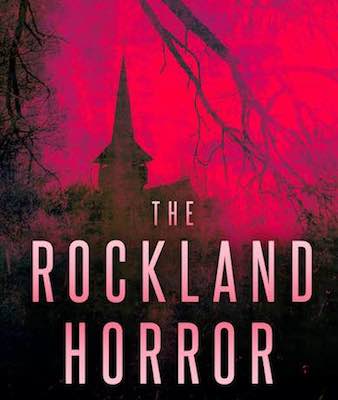

The Rockland Horror 2 is available on Amazon!

(But you’ll want to read the first book in the series, The Rockland Horror, first.)

Both books are filled with murder, betrayal, evil spirits, zombies, supernatural monsters, and characters you’ll never forget!

Here’s a sample chapter from The Rockland Horror 2:

Chapter 1

August 1882

Ellen Briggs, née Ellen Sanders, was in her own house, and she was absolutely terrified.

Of course, this was not really her house, was it? It was her marital residence, where she now effectively lived in a state of captivity.

Not to mention…absolute terror.

She had married Theodore Briggs—railroad tycoon, necromancer, and murderer—only a few months ago.

In the early days of the marriage, Briggs had warned her: Stay out of unfamiliar rooms. Although the house was not old, it was home to many old secrets, Briggs had explained.

But she had forgotten his warning, in light of all that had happened since then…

Today Ellen had been wandering through the first floor of the massive house. Since her escape attempt earlier in the summer, Briggs seldom allowed her leave. But she could not sit still within these walls. If she remained in one place, she would go completely mad.

So today she had gone wandering, even though she had known better.

That was how she came across the undead child…

The door to the room containing the undead child was located adjacent to the first-floor ballroom. Ellen had opened the door, not realizing that the room connected to the basement via one of the home’s labyrinthine internal tunnels.

She reckoned that only later—after it was too late.

It was in the basement that her husband kept his worst secrets. Bodies were buried in the basement—and they didn’t always stay buried. Sometimes, they found their way to other parts of the house…

Nevertheless, this miscellaneous room had seemed harmless enough when she had first entered it. Heavy draperies were drawn on both of the room’s high windows, but some late afternoon sunlight filtered through.

The room seemed made for casual exploration. Various works of art had been stored within it. Paintings bound in frames, but not yet hung, stood stacked against all four walls.

Throughout the floor, in a random arrangement, were various statues: of nymphs, cherubs, and Greek deities. There was one life-size replica of the Venus de Milo. There were waist-high vases, and teak dividers carved in what looked like Turkish patterns.

The fortunes of Ellen’s husband were vast. He had no doubt purchased most of these items in bulk from a broker, with the intention of placing them around the house at a later date.

That work might have been left to Juba, the maidservant whom her husband had ordered killed, for her part in Ellen’s escape attempt. That same escape attempt had also resulted in her husband murdering Wilbur Craine, her former beau and would-be rescuer.

As she made her way through the cluttered room, Ellen endeavored to push those thoughts from her mind. She couldn’t think about Juba now. And certainly not about Wilbur.

She was kneeling down on the hardwood floor, admiring one of the paintings leant against the wall, when she heard something shift from a corner of the room.

Ellen immediately looked away from the landscape painting, toward the movement. She stood up. Something had stirred behind the teak screen in the room’s far corner, near one of the windows.

The teak screen was suspended above the floor on a set of wooden legs. In the gap between the screen and the floor, Ellen could see two small feet, clad in simple leather shoes. The shoes were caked with dried mud.

The feet moved toward the edge of the screen, but not in proper steps. One foot dragged behind the other.

A small figure stepped out from behind the screen. It was short, between four and five feet tall. The very sight of it was absolutely terrifying.

Chapter 2

Ellen immediately recognized the figure as a child. And at the the same time, this was not a child at all.

There was an unholy, yellowish glow in the thing’s eyes. Ellen had seen this glow in the eyes of Ni’qua, Briggs’s undead first wife. Ni’qua lurked around the house, and appeared before Ellen when least expected.

But this child was even worse. Ni’qua had been dead for decades, after all. This victim had been taken only months ago.

“Come play with me!” the thing croaked hoarsely, through rotting lips.

Ellen didn’t speak. There was nothing to say to this thing; and that would only slow down her escape, anyway.

She needed to think.

No—she needed to get out of this room. Immediately.

Ellen turned and bolted for the door.

Behind her she could hear dragging footsteps. The child was giving chase, but Ellen moved much faster, owing to the damage Briggs and his valet had done to the child’s injured leg prior to burial.

The thing was now cursing at her—using the vocabulary of some ancient language that she did not understand.

A few more steps, and Ellen was at the threshold, then beyond it.

She had never moved faster in her life, she thought.

Then she was on the other side of the doorway.

She did not want to turn around, did not want to look back. She knew, however, that it would be necessary to close the door, lest the thing pursue her out into the hallway.

When Ellen turned around, the creature was within sprinting distance of the doorway, if not for the ruined leg.

As Ellen reached for and grasped the doorknob, an expression of bottomless rage contorted the already rotting and grimacing face. This evil before her was intelligent; it knew what she planned to do.

Ellen ignored her terror, for the time being, forced herself to focus.

She yanked on the doorknob, and slammed the door shut behind her.

Then she twisted the external catch on the doorknob. Another strange thing about this house: Her husband had designed it so that many of the rooms locked from the outside.

That done, the thing was effectively contained inside the room. A second later, there was a loud thud, as a creature that had once been a human child slammed into the closed door.

“Let me out!” it roared. The voice was ancient, booming. It echoed against the walls of the hallway.

Ellen stepped away from the closed door. She looked in one direction, and saw that the hallway terminated there in a bare wall.

In the other direction, from which she had arrived here, the hallway ended in another doorway.

With the thing still pounding on the door of the storage room, still cursing in that hideous language, Ellen made her escape through the high-ceilinged hallway. She fled toward the doorway.

There was a locking door here, too. Ellen closed it behind her and locked it.

The undead child was now locked behind two heavy doors. Was that enough to make her safe?

She shook her head at the very notion. There was no such thing as true safety in this house.

View the book on Amazon!