Amazon has expanded the Kindle Unlimited FREE trial to two months.

This is therefore an opportune time to try the service.

Many of my books are in Kindle Unlimited, including my latest, Venetian Springs.

Welcome to the website of author Edward Trimnell!

Amazon has expanded the Kindle Unlimited FREE trial to two months.

This is therefore an opportune time to try the service.

Many of my books are in Kindle Unlimited, including my latest, Venetian Springs.

A reader recently asked me via email why I chose to set 12 Hours of Halloween, my coming-of-age horror novel about three friends who battle supernatural forces on Halloween Night, in 1980 instead of the present day.

Good question.

There are two reasons behind this choice.

First of all: there’s the generational factor.

What I mean by this is: I know my limits.

Although 12 Hours of Halloween is a supernatural tale, it is also a coming-of-age story. This means that it involves getting into the “head space” of the story’s adolescent protagonists.

Some aspects of adolescence are universal. But others are heavily dependent on changing generational factors.

I’m a member of Generation X (born in 1968). This generation reached the early teen years of adolescence around 1980—the year in which 12 Hours of Halloween is set.

I figured that I could depict the adolescent experience in 1980 most accurately, because I actually lived it. (I turned 12 in 1980.) I’ve written before about the perils of middle-age adults writing about the present-day teen experience: During the 1980s, most of the teen films were written by Baby Boomers; and certain aspects of these movies seemed anachronistic, because the scriptwriters were actually writing about the teen experience of the 1950s and 1960s—even though they thought they were writing about the 1980s.

Another reason I chose to set 12 Hours of Halloween in 1980 is: The past is haunted.

The year 1980 is now 40 years in the past. (1980 was 35 years in the past when I published 12 Hours of Halloween in 2015.)

That is recent enough to be accessible to most readers, but distant enough to be surrounded by a certain haziness.

That year is not quite like our own. After all, in 1980, there was no Internet, and no cell phones. We had television, but cable TV was still a “new” thing.

It isn’t difficult to believe that in 1980, wayward spirits and vengeful supernatural creatures walked the earth in one Ohio suburb—just like in the book.

***

Want to read 12 Hours of Halloween? You can preview the book here on this site, or get it on Amazon (available in multiple formats.)

Given the passing of Neil Peart last week, I’ll probably have a few Rush-related posts in the upcoming days.

The above video contains a particularly insightful interview from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Topics covered include: Neil Peart’s drumming, and (of particular interest to me) his song-writing.

The man interviewed is, like me, a lifelong Rush fan in his fifties. Unlike me, he’s also a musician.

At the 2:20 mark, he says that Rush was one of those bands that, “You either got them or you didn’t; and if you did ‘get them’, you became a lifelong fan.”

Well put. I couldn’t agree more.

Another New Year’s Eve has arrived. I know that many of you will be consuming large quantities of alcoholic beverages tonight.

Not me, though. I haven’t consumed alcoholic beverages very much at all since New Year’s Eve 1986. But that night I did consume a lot of wine, beer, vodka, and other spirits.

For the last time.

I was eighteen years old on 1/31/86. The drinking age in Ohio had just been raised from 18 to 21. But what did I care? In fact, I hadn’t cared much about such niceties since 1981, when I’d begun experimenting with alcohol at the age of 13.

Hey—it was the Eighties! There was no helicopter parenting back then. Moreover, in those freewheeling times, shopkeepers could sometimes be persuaded to sell beer or wine to underage teens who looked mature. I started shaving at the age of 14.

And as for the hard stuff….well, let’s just say that not all parents minded their liquor cabinets, let alone installed locks on them.

Between the 8th grade and my high school graduation, I did my share of drinking. I wasn’t a lush, mind you, but I managed to try everything from beer to bourbon. (Rum was the only drink that I never tried, and I’d always wanted to shout, “Yo, ho, ho, and a bottle o’ rum!” with a pirate’s inflection, while holding a bottle of Bacardi or Captain Morgan.)

I quickly learned an unpleasant truth about drinking and me: I didn’t like hangovers.

Hangovers manifest themselves differently for everyone. For me, a hangover invariably entailed projectile vomiting, extreme fatigue, and the sense that my head had just been used to ring a church bell. A hangover left me feeling really bad—for at least one day, and probably two.

By New Year’s Eve 1986 I already knew that alcohol affected me this way. But I was eighteen years old. Since when have eighteen year-olds been fast learners? I had graduated from high school the previous spring, and a girl from my class (one I sort of liked) had invited me to a New Year’s Party. I therefore had to attend. And being a typical teenage herd animal, I had to drink—because that’s what everyone else would be doing.

I don’t know exactly how many drinks I had that night. I got drunk enough, however, that the operation of a motor vehicle would have been out of the question. (I had arranged for a ride that night, so no—I wasn’t drinking and driving; nor did I ever do that.)

The next morning, 1/1/87, my first thought upon waking up was that eighteen years was plenty long enough for any one person to live. I should just die now, and be done with it.

I had a bad hangover—my worst one to date.

I got out of bed and went for a run in the frigid morning air. This helped—to a point. I felt decent as long as I kept running. The thing about running, though, is that you eventually have to stop. Within a few minutes of completing my run, I was feeling just as lousy as I had upon waking up.

I still lived with my parents at the time. They decided to celebrate the New Year by going out for breakfast. And of course—I readily agreed to tag along when they invited me to join them. (Like I said, most 18 year-olds are not quick on the uptake.)

As soon as we were seated in our booth, I wanted to leave. I realized that I wasn’t up to eating anything. My parents, though, wanted their breakfasts. My mother insisted on ordering a breakfast consisting of eggs, hash browns, sausage, and gravy. If your stomach is up to snuff, that might be a delicious combination. But what if you have a hangover, and you can barely keep a glass of water down? In that case, the aroma of a typical “country breakfast” platter is a barf-inducing olfactory concoction.

My parents, being no fools, saw what was up. So did our sixty-something waitress, who poked fun at my misery while I sat there without breakfast.

When I arrived back home that morning, I had an epiphany: I’d been an idiot. Binge drinking was nothing more than self-induced misery.

And no, it wasn’t “cool”. What is so cool about projectile vomiting?

I clearly remember the moment—on January 1st, 1987, in which I said, “never again”.

I made a vow never to put myself through that again. More than thirty years later, I still haven’t. I’ve never consumed alcoholic to excess since that night.

I have had the occasional glass of wine or bottle of beer. But even these are rare. (My most recent tipple was a beer at a trade show in 2002.) Alcoholic beverages and me just don’t mix. I haven’t missed them.

And besides—now that I’m more than old enough to drink legally, what’s the point?

I was a member of the original Star Wars generation. I remember sitting in the cinema with my dad, in the summer of 1977, watching that opening text crawl:

“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away….”

I was instantly hooked. There was something special about being a kid in 1977, when Star Wars was brand new, and there was one movie, instead of a gazillion of them.

I also became one of the millions of child consumers who fueled the Star Wars licensing boom.

Collecting action figures would be an extremely nerdy activity for me today (pathetic, actually—I’m in my fifties); but at age nine I was just fine with that. I had many of the Star Wars action figures.

But I especially liked the Star Wars trading cards.

I had always felt left out of the baseball card trading craze of the 1970s. (I never minded spectator sports, but to this day I’m not crazy about them.)

But Star Wars cards, yes, I loved those.

Each card featured an iconic scene from the movie. Also, each pack of Star Wars cards contained a sticker (very useful for adorning my looseleaf binder in the fourth grade).

Oh, and a stick of gum—just like the baseball cards.

I doubt that kids bother with any sort of trading cards anymore. It’s all about i-this and i-that nowadays.

But forty-odd years ago, if you were a kid who was crazy about Star Wars, it was a lot of fun to collect those cards.

If you haven’t read Revolutionary Ghosts yet, here is your chance to get it on Amazon Kindle for less than a buck.

Revolutionary Ghosts is a coming-of-age horror tale set in 1976…

The year is 1976, and the Headless Horseman rides again. A dark fantasy horror thriller filled with wayward spirits, historical figures, and a cool 1970s vibe.

Perhaps you read my recent critique of the Apple Store concept and thought that I might be a complainer.

Well, a writer at ZD Net had a similar experience: I went to an Apple store to buy an iPhone 11, but no one would talk to me

The article describes “a little chaos in Apple retail right now”.

Based on my visit last week, I would describe that assessment as a very polite understatement.

This was one of the big teen movies of my youth. I saw it when it came out in the mid-1980s. I recently watched it again as a middle-age (51) adult.

The basic idea of The Breakfast Club is immediately relatable: Five very different teens (a nerd, a jock, a princess, a basket case, a hoodlum) are thrown together in the enclosed space of their high school’s library. They are then forced to interact over the course of a day-long detention period on a Saturday.

This is a small drama, but also a much larger one: The setup for the movie provides a concentrated and contained view of all teenage interactions.

I liked The Breakfast Club, for all the usual reasons that millions of people have liked the movie since it first hit cinemas in February 1985. Everyone who has ever been a teenager can relate to feeling awkward and misunderstood; and The Breakfast Club has teenage angst in spades. The cast of characters is diverse enough that each of us can see parts of ourselves in at least one of these kids.

The Breakfast Club is free of the gratuitous nudity that was somewhat common in the teensploitation films of the era. There is no Breakfast Club equivalent to Phoebe Cates’s topless walk beside the swimming pool in Fast Times at Ridgemont High. (There is a brief glimpse of what is supposed to be Molly Ringwald’s panties. But since Ringwald was a minor at the time, an adult actress filled in as a double for this shot.)

Nor are any of the actors especially good-looking or flashy. They all look like normal people. No one paid to see this movie for its star power or sex appeal. The Breakfast Club succeeded on the basis of its script, and solid acting and production values.

I enjoyed the movie the second time around, too. I have to admit, though, that teenage self-absorption can seem a little irksome when viewed through adult eyes. Even the teenage self-absorption of one’s own generation.

I’m the same age as Michael Anthony Hall and Molly Ringwald; we were all born in 1968. The other actors in the film are all within ten years of my age. Nevertheless, this time I was watching their teenage drama unfold as an older person—not as a teenager myself. Teenage drama is, by its very nature, trivial (and yes, a little annoying) when viewed from an adult perspective.

The movie also makes all adults look corrupt, stupid, or craven—as opposed to the hapless and victimized, but essentially idealistic and blameless—teens. Every young character in The Breakfast Club blames his or her parents for their problems, and these assertions are never really challenged.

We get only a few shots of the parents, when the kids are being dropped off for their day of detention. The parents are all portrayed as simplistic naggers.

The teens’ adult nemesis throughout the movie, Assistant Principal Vernon, is a caricature, a teenager’s skewed perception of the evil adult authority figure. The school janitor, meanwhile, is no working-class hero–but a sly operator who blackmails Vernon for $50.

One of the reasons you liked this movie if you were a teenager in 1985 is that it flattered you–without challenging your myopic, teenage perspective of the world. If you weren’t happy, it was probably because of something your parents did, not anything that you did–or failed to do.

That may have been a marketing decision. Who knows? The Breakfast Club goes out of its way to flatter its target audience–the suburban teenager of the mid-1980s. I suppose I didn’t see that when I was a member of that demographic. I see it now, though.

-ET

Thanks to those of you who purchased 12 Hours of Halloween during the recent $0.99 sale. The sale was a big success, when combined with the promotions that I ran for it on several sites.

I’ve got some more fiction in the works for Amazon/Kindle Unlimited publication. Remember that I also have a new story here on the site, “I Know George Washington”.

“I Know George Washington” will eventually find its way into one of my upcoming anthologies. My plan, though, is to keep this story–along with many others–ever-free here on Edward Trimnell Books (or in Kindle Unlimited)

For me, publication is about more than just Amazon. I am also a big fan of the ezine/webzine concept. That means lots of stories and other content here on Edward Trimnell Books, for you to read online.

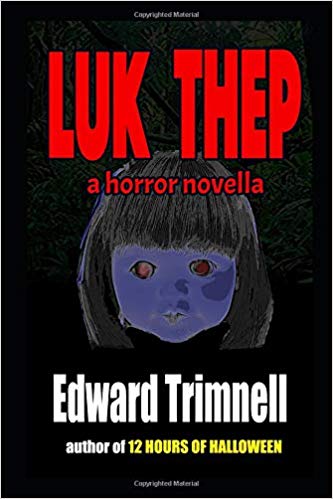

If you haven’t read my novella Luk Thep, this is your chance to read it for FREE.

I wrote this novella in early 2016, after I read this article in The Economist.

I haven’t promoted Luk Thep as aggressively as some other titles, but readers have generally liked it. Check it out on Amazon!

I own several HP Lovecraft collections, but this one is my favorite: The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre . This volume was published in 1987.

I’ve bought it twice: Once in 1988 (that copy is long since gone); and I bought a replacement copy about two years ago.

This collection has all the stories that the newcomer to Lovecraft really needs, including “The Shadow over Innsmouth” and “The Dunwich Horror”.

Another feature of this collection is the excellent introductory essay by Robert Bloch.

Over the past week or so, the weather here in Southern Ohio has been growing gradually cooler, after a brutal heatwave throughout most of July and August.

Today we had a delightfully cool, overcast morning.

Autumn is my favorite time of year, and the time when I tend to be most productive. (My most sluggish time of the year is the dog days of high summer.)

Let summer end, and let fall begin in earnest.

Only 54 days until Halloween!

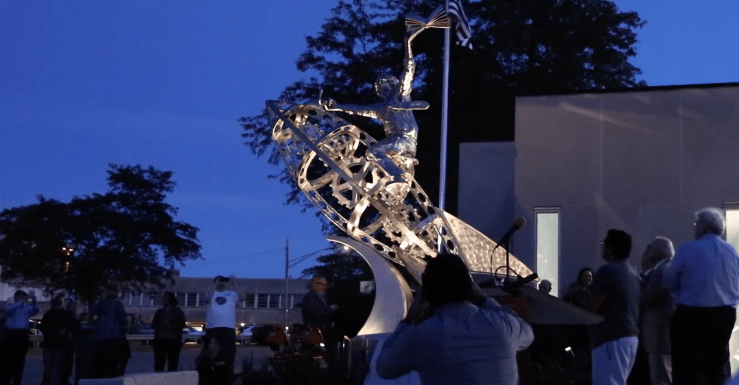

Waukegan Public Library unveils Ray Bradbury statue on ‘Fahrenheit 451’ author’s birthday

I’ve read Fahrenheit 451 several times. This is a short novel, and it won’t take you long to read. (Bradbury was more of a short story writer than a novelist. The novels that he wrote tended to be on the short side, too.)

Some of you have been asking my opinion regarding new Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt’s plan for the struggling book retailer.

Daunt plans to make B&N stores stripped-down versions of what they currently are. The model here is the airport bookstore on one hand, the local, neighborhood bookstore on the other.

In other words, small bookstores that carry about the same inventory as the book section of the nearest Walmart, Costco, or Kroger.

So why do you even need a bookstore, if Walmart already stocks about the same number of books?

Daunt is British, and this might be a viable strategy for the British retail market, which is decades behind that of the United States.

It isn’t a winning strategy for the US, where Amazon dominates by virtue of its wide selection, low prices, and economies of scale.

Daunt clearly has no plan to compete with Amazon. He plans to compete with…small neighborhood bookstores that have already gone out of business in most of the U.S.

Forgive me if I’m underwhelmed.

Just in time for late summer reading, I’ve added these horror titles for you to enjoy FREE in Kindle Unlimited:

(Click the links to view them on Amazon.)

The year is 1976, and the Headless Horseman rides again. A dark fantasy horror thriller filled with wayward spirits, historical figures, and a 1970s vibe.

Halloween night 1980: The suburbs are haunted, as three young friends endure twelve hours of nonstop supernatural terror. Will they survive the night?

Would you risk your life and sanity on the most haunted road in Ohio for a $2000 prize?

16 horrific tales filled with monsters, ghosts, and deadly people. For fans of Stephen King’s short story collections.

An American executive in exotic Thailand. An evil spirit that follows her home. Supernatural mystery and terror on two continents.