Approximately one hour later, they arrived at their destination, about five miles south of the Columbus metro area. It wasn’t what Evan had expected.

The scenery here was still rural. There were plenty of cornfields, high and dark green in their late summer lushness. On the far, flat horizon, Evan could see a scattering of barns, and even a grain silo.

Following the directions generated by the Camry’s GPS system, Evan guided the car off the interstate at the designated exit.

“Is this it?” Evan asked, doubtful.

“This is it,” Hugh affirmed.

In the rearview mirror, Evan saw Amanda glance up at him, mildly annoyed.

The exit took them around a long, sloping curve that dead-ended in a two-lane highway. The android voice of the GPS told Evan to turn right.

“That’s Lakeview Towers over there,” Hugh said, pointing in that direction. Evan made the right turn; and as the Camry traversed the rural highway and crested a small hill, the office complex called Lakeview Towers came into view.

The glass-plated, ultramodern architecture looked more than a little out-of-place here in the middle of the Ohio countryside. True to its name, Lakeview Towers consisted of four towers that must have been ten or twelve stories high. The towers were connected by a series of shorter segments that were perhaps three stories in height each.

“It’s big,” Evan observed.

“Yes,” Hugh said. “It’s big.”

Evan kept driving.

How many office suites would there be in Lakeview Towers? Hundreds, at least. A lot of space to rent this far south of Columbus, Evan thought.

They continued to approach at about thirty miles per hour. Lakeview Towers seemed to grow even larger as it drew closer.

This was only an optical illusion, Evan decided. Down at the exit, the structure had been partially obscured by the topography. As they came upon the entrance to the main parking lot, though, Evan found himself growing more impressed by the scale of the office complex. The morning sunlight glinted off the glass-plated columns.

Evan saw a massive shadow pass over one of the glass columns. It was fleeting—as if something huge were flying by overhead.

He looked up through the Camry’s windshield. A shadow that large could only have been cast by a low-flying airplane.

Or a very, very large bird.

But Evan saw nothing unusual in the blue sky above the two-lane access road.

The shadow came from a cloud, he concluded.

Returning his attention to the road, Evan turned into the parking lot. The immaculately manicured “campus” (as it was now trendy to call corporate facilities) was filled with plenty of green space between the parking areas. A pair of artificial ponds dominated the weed-free lawn opposite the main entrance. In the middle of each pond was a water jet.

Evan also noticed a small gaggle of white geese distributed between the two bodies of water. This was a good place for the birds, he figured: There would be no hunters to disturb them here.

Had a goose cast that shadow? Evan wondered. No. Impossible. No way a goose could throw a shadow like that.

Then he recalled what he had concluded: The shadow had been cast by a puffy white cumulus cloud. There were plenty of those in the sky today.

Fortunately, there were plenty of open parking spaces, too. Evan found a space located reasonably close to the main entrance, adjacent to the two ponds, and parked.

Before killing the engine, he looked at the dashboard clock: It was 8:37 a.m. They had time to spare before the appointment, even with factoring in the time needed to set up the projector for the PowerPoint presentation.

Evan stepped out of the car, then leaned down to smooth his tie and his white dress shirt in the driver’s side exterior mirror. The right breast of the shirt bore a monogrammed “MSS”, and the logo for Merlesoft Software Systems—a generic computer motif.

Hugh and Amanda exited the vehicle as well. Finding the key fob in his pocket, Evan pressed the button that opened the trunk automatically. He reached down to lift the projector out of the trunk.

That was when Amanda pounced.

***

“Did you remember to include a slide containing the timeline of the four quotations we submitted?” Amanda asked, not quite casually.

Evan stared back at her, nonplussed. He had remembered everything, or so he had thought. He had spent hours preparing the PowerPoint slides, and additional hours preparing himself to deliver a flawless sales presentation.

But he had not thought to include a slide depicting the timeline of the quotations.

He could easily imagine what Amanda wanted: A visual representation not only of the successive changes in pricing, but also something that summarized the technical change points. This would demonstrate how Merlesoft had recommended cost-effective changes to the original specifications provided by Rich, Litchfield, and Baker.

It wasn’t a bad idea; but it was the one thing he hadn’t thought of—and the one thing that Amanda saw fit to remember, less than thirty minutes before game time.

“No, Amanda,” he said, pausing with his hand on the handle of the projector’s carrying case. “I didn’t think to include a slide showing the timeline of the quotations we submitted.”

As soon as the words were out of his mouth, Evan realized that he had delivered them flippantly. This hadn’t been his intention. He had meant to express the idea of, “I see what you’re getting at, but no—I forgot!”

That admission would be bad enough; it would add to the long list of black marks against him. This was a list that Amanda Kearns maintained, he was certain, in one form or another.

But now it was clear that Amanda perceived his words as a challenge to her authority, the one infraction that any manager at Merlesoft despised more than anything else.

“Don’t think that I don’t hear the resentment in your voice, Evan. I wouldn’t have to ask you this sort of thing, if only you would think of it yourself.”

Evan felt a wave of anger and resentment suddenly surge through him. Amanda was addressing him as if he were a slacker, a ne’er-do-well. The truth was that he had thought of many things. He just hadn’t thought of that particular thing—the one thing that she had chosen to ask about.

And in all the sales presentations prior to this one, he had never prepared a visual timeline of the quotations. Early quotations, in fact, were generally regarded as irrelevant. Final sales presentations usually focused on the most current quotation.

He now saw what Amanda was doing to him: She was using the process of elimination to trip him up. She had rigged the game so that he would inevitably lose it. There was no way for him to win in a situation like this.

Finally his temper snapped. “Do you want me to create the slide right now? I have my laptop computer back here.”

“Evan,” she replied with an air of calm superiority. “We both know that there’s no time for you to do that, when we have to meet with the client in a matter of minutes. My point was that it should have been done earlier.”

That was when Hugh intervened.

“Whoa, whoa,” he said, gently squeezing Evan’s arm and interposing himself between Amanda and him. “There’s no time now, buddy. She’s right about that. Let’s just focus on doing the best we can with the presentation we’ve got now. We can talk about next time later on. As it stands right now, we’re going to be on in about fifteen minutes.”

Evan nodded silently, allowing himself to be mollified by Hugh.

Amanda, too, allowed this to be the last word about the matter—for now. (There would doubtless be further recriminations later—especially if an order from Rich, Litchfield, and Baker failed to materialize.) Evan noted (and not for the first time) that Amanda sometimes allowed Hugh to exert a subtle form of authority, as long as he didn’t step on her toes in the process.

Loaded up with gear and presentation materials, they walked toward the double doors that formed the front entrance of the Lakeview Towers office complex. Evan could see their reflections bobbing in the glass face of the building.

He again recalled the vague warning that Hugh had given him while they were sitting in the McDonald’s—or the warning that Hugh had tried to give him.

And then something else happened.

***

Evan saw a reflection in the glass of the front entranceway. The reflection was distorted by the glass, the sunlight, and the angle; but it was unmistakably there.

And it was very close to the three of them.

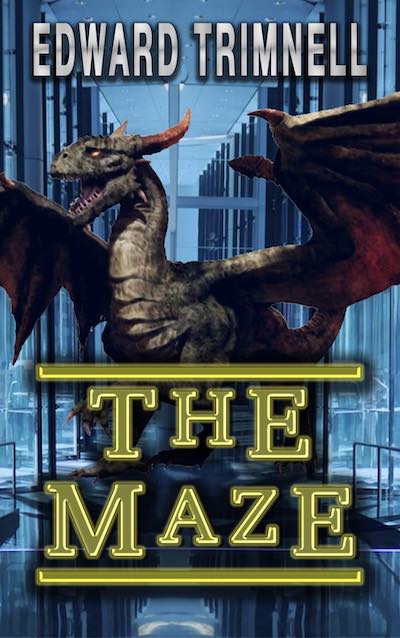

It was a large, winged beast—not quite a bird, and not quite a mammal or a reptile. A brown-toned monstrosity that might have been covered with fur, or maybe with scales.

It flew behind and past them near ground level. In that fraction of an instant, Evan discerned a tapered snout filled with long, jagged teeth. A stout body topped by two batlike wings.

And then, behind the beast, a long tail, twitching back and forth as the creature swooped low toward the earth.

A second later, it was gone.

Evan whirled around, nearly dropping the load in his arms. He clutched the projector just as it was about to slip away from him.

When turned around, Amanda looked straight at him.

“Something wrong, Evan?”

There was plenty wrong. That had been no ambiguous shadow, prone to a half-dozen explanations and interpretations. That had been something—if only evidence of his own overstressed mind, now subjecting him to paranoid delusions.

“No,” Evan told Amanda. “Nothing’s wrong.”

“Well, then,” she said icily, “what say we keep going?”

***

Evan was still shaken, but he turned back around and kept going.

Don’t try to process that now, he told himself. That thing you just saw—you can think about that during the long drive back to Cincinnati.

And it was just your imagination, anyway, right?

Sure. That was all it had been.

They pushed through the entranceway. Evan exercised extra caution so as not to drop anything.

Once again, he imagined the projector slipping out of his hands and crashing to the floor. Then the whole sales presentation would be ruined, all because of his momentary blunder, his failure to anticipate. The resultant recriminations would be unbearable.

Even worse than that reflection he had just hallucinated in the glass.

The lobby was state-of-the-art, contemporary office chic. There was wall-to-wall, low-pile grey carpeting. Soft, frameless chairs in the waiting area. Strategically spaced, abstract paintings.

The three of them headed immediately to the wood-paneled security enclosure, where two security guards—a heavyset woman and a rather frail-looking older man—sat beneath soft cove lighting.

Amanda motioned for Hugh and Evan to complete the sign-in procedures before her. She wanted to check the messages on her phone before signing in, apparently.

She likely wanted to check for messages from Oscar, Evan thought.

While Evan and Hugh were pinning on their temporary access security badges and waiting for Amanda to finish with the security guards, Hugh pulled him aside and said discreetly:

“Stick with me while you’re here. And don’t talk to any other security guards you might happen to see here. Only these two at the front desk are okay.”

Once again Evan found himself wondering if Hugh was suffering from some sort of a delusion, or possibly setting him up for an elaborate practical joke.

What I just saw, that was my imagination, he reminded himself. The power of suggestion. There was nothing real to it. Couldn’t have been.

“You’re really serious about wanting me to not wander off in this building, aren’t you?” Evan asked.

He smiled in an attempt to break the tension of the quarrel with Amanda, and the imagined reflection in the glass. He needed to calm the butterflies in his stomach. He often felt a slight degree of nervousness just before a big client pitch, but his jitters were now approaching a terminal level. Too much to think about.

And Hugh was making it worse.

“Are you going to tell me what this is all about?” Evan asked, hoping for some levity in return. Maybe Hugh would break the joke now. Because this had to be a joke.

“Evan,” Hugh said, his voice low and deadpan. “You saw something, didn’t you? Just now, as we were coming in.”

Evan felt his heart leap again.

“Did you—?”

“That’s not important,” Hugh replied. “I don’t have the time to explain this to you now. But if we make it out of here okay, then I promise you I will.”

“What the hell are you talking about? ‘If we make it out of here okay’?”

“Maybe nothing more than my imagination, buddy. But maybe something. In any case, safety is the best policy. Just remember what I said.”

Evan opened his mouth to ask another question. Then Amanda appeared, her temporary visitor badge pinned to her blouse.

“Are you ready, gentlemen?”

“We’re ready,” Hugh said, answering for both of them. “Follow me. I’ve been here before, after all.”

***

Evan and Amanda followed, as Hugh led them down a hallway adjacent to the lobby, toward the law firm’s first-floor office suite.

Evan was conscious of the combined weight of the portable projector and his laptop. Amanda was carrying her briefcase, and a satchel that contained the handout materials for the presentation.

Hugh, meanwhile, was carrying only his attaché case. Given his heart condition, neither Evan nor Amanda would have expected him to carry anything more.

They passed by a number of office suites, Hugh leading the way. Each office suite was enclosed behind a stately wooden door. There were windows on both lateral sides of each door. This made it possible for Evan to look into the suites. He saw comfortable-looking office settings with modern office furniture, but no people.

Strange that there were no people. How much vacant space was there in Lakeview Towers? It seemed that most of the complex was vacant.

Miles and miles of space, Evan thought, for no reason that he could fathom.

On and on forever…

A wave of unexpected dizziness hit him. He nearly stumbled at one point, as he felt abruptly light-headed. He feared that he would drop the projector—for real this time. He experienced a moment of genuine panic, a sense that he was about to faint.

Then he quickly recovered and righted himself. As suddenly as the odd feeling had come upon him, it was gone now.

Since he was walking behind both Amanda and Hugh, neither of them had noticed, he was glad to see.

What’s wrong with me?

He detected a faint whiff of something unpleasant in the air. It was a burnt, sooty smell—not exactly organic, but not exactly chemical, either. Perhaps it was this odor that had made him suddenly dizzy. It might be the result of a problem with the ventilation system here.

Evan felt almost himself again when they finally arrived at the door with the decorative brass plaque that read: “Rich, Litchfield, & Baker, Attorneys at Law.”

A receptionist was stationed immediately inside the suite. Her desk was in the center of a small waiting room. The receptionist—a young, redheaded woman who caught Evan’s eye—informed them that they could proceed directly down the rear hallway to meeting room 1A—the law firm’s media room.

Meeting room 1A contained a large oblong oak table, surrounded by about a dozen high-backed, leather-padded chairs. The attorneys had spared no expense to make their office space attractive, it seemed. At the far end of the room, Evan spotted the roll-down screen that he would use to project the PowerPoint presentation.

Being careful not to make direct eye contact with Amanda, he went about setting up the projector and connecting it to his laptop. Luckily, there were plenty of electrical outlets in the room, and he had brought extra lengths of extension cord.

Hugh had warned him not to talk to any other security guards. Now why would Hugh say something like that? What did he mean? Evan could have asked him—if not for Amanda’s hovering presence.

Evan had just finished setting up the equipment for the presentation when the lawyers filed in. Introductions were made.

Evan was still feeling a bit light-headed, and he was still more than a little angry at Amanda. He was also dreading the inevitable follow-up confrontation that would surely result from today’s exchange with his boss. When they returned to the Merlesoft office, there would surely be hell to pay—in one form or another.

But now he had a job to do. He would spite Amanda Kearns by doing it to the best of his abilities.

***

“First, I want to thank all of you for taking the time to hear Merlesoft’s presentation today,” Evan began.

He was the only one standing in the darkened room. Seated closest to the projection screen around the oblong table were four attorneys from Rich, Litchfield, and Baker. They were joined by the firm’s accountant, and an information systems person. Finally, Amanda and Hugh were seated toward the back, behind all the client representatives.

The first PowerPoint slide featured an image of Rich, Litchfield, and Baker’s logo alongside an image of the Merlesoft logo. The idea was to suggest that the two companies were in an ad hoc union of sorts.

This was a standard bit of sales psycho-strategizing. The idea was to spin the (hopefully) imminent purchase order as a partnership—not a transaction. Then the client representatives wouldn’t feel that they were on the receiving end of a sales pitch. Even though it was very much a sales pitch.

While not exactly sinister, the whole thing seemed vaguely duplicitous. I’m no more a salesperson than a software guru, Evan thought.

Nevertheless, he launched into the presentation, clicking through the slides with the projector’s remote control. He had studied his lines so much in advance that he was almost able to run on autopilot. This was a good thing—as the dizziness that he had briefly experienced in the hallway was now returning with a vengeance.

And once again he was aware of that peculiar smell. The odor might best be described as a mixture of gasoline fumes and burning vegetable matter.

The smell was all around him now, as if it were coming through the air ducts.

The dark room and the soft glare of the projection screen began to shift before his eyes. He knew that his voice was wavering, because everyone in the room had turned their attention away from the screen at the front of the room. They were looking at him—no doubt wondering what was wrong.

That was a question that was acutely troubling him, as well. The partially illuminated faces around him began to shift, to melt into the darkness. When he tried to read the slide that was currently projected up on the screen, the words ran together.

I’ve got to get out of this room, he thought. Something’s wrong with me.

Then an additional complication arose. He was acutely aware of the large breakfast that he had eaten—the one that was supposed to give him energy to concentrate on his presentation. It was churning and bubbling in his stomach, threatening to erupt and spill out onto the meeting table.

To pass out before a roomful of customers would be bad enough. To upchuck in front of clients would be an unmitigated disaster.

Evan made a snap decision. He placed the projector remote on the table between Hugh and Amanda. One of them would have to take over.

“You’ll have to excuse me,” he announced to the room. “I’m afraid that I’m going to be sick.”

Sample chapters list