First and foremost, this is not a post from a luddite who wants to smash the machine overlords. I grew up in a completely analog world. I’m now as digital as anyone out there. I don’t long for the days of IBM Selectric typewriters and rotary phones.

Similarly, I’m not anti-AI. Yes, I was skeptical at first. Then I tried it. I now use AI for all manner of things; AI has become an essential element in my toolkit.

This doesn’t present any real cognitive dissonance for me. Drop me into a public library, circa 1978, and I’ll be able to find information just fine, using the library’s physical card catalog, and the Dewey Decimal System. If the internet ever goes down, I’ll be just fine without it. I got by without it well into my adult years, after all.

But why would I want to do that, when better tools are available? AI is invaluable for research and data analysis, which have their applications in both fiction and nonfiction. I’m leaning heavily on AI to gather research for a new nonfiction title I’m currently working on.

My perspective—as a digital nonnative who has subsequently embraced most things digital—gives me a unique perspective. I don’t fear technology. But I recognize that all technology, no matter how advanced, has its limits. That’s true of a 1993 Toyota Camry. It’s also true of AI.

In case you haven’t heard, AI can write prose for you, too. The question is: should you let AI write your books, through a series of guided prompts?

No. And I’m going to tell you why. My assessment is based not on hifalutin artistic ideals or the collective sentiments of “the writing community”. (I do not care two hoots about the collective sentiments of the “writing community”, and I never have.) My assessment is ultimately based on pragmatism.

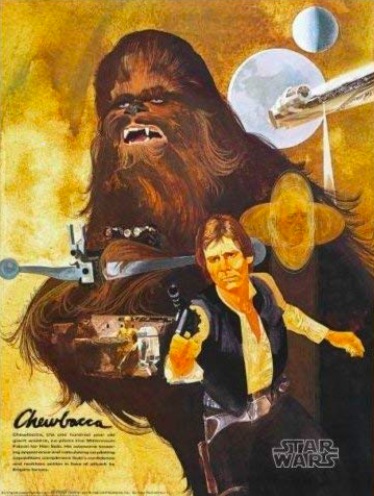

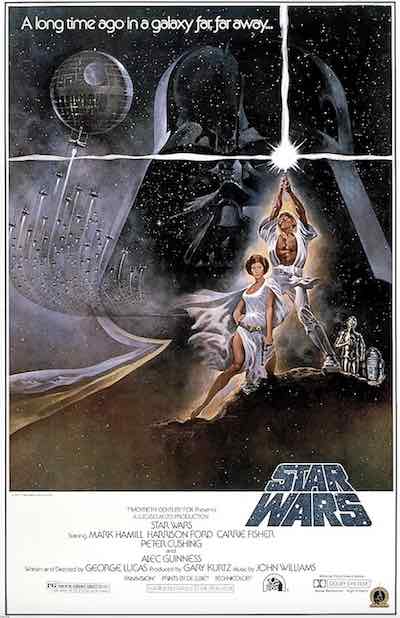

Long-form AI prose, like AI visual “art”, is easily discernible to the practiced eye. After two years of looking at AI artwork in my Facebook feed, I can now spot the stuff from a mile away.

After reading a handful of passages of AI-written fiction over the past two years, I can now distinguish AI-written prose, too.

AI prose is not always laughable. But it never rises out of what Masahiro Mori identified as “the uncanny valley”. The “uncanny valley” is the uncomfortable feeling we get when something is humanlike—but not quite human.

AI prose might be fine for product descriptions on Walmart.com, or topic summaries for research purposes. It isn’t good enough for fiction.

A word of caution here. If you read a passage of AI-generated fiction and say, “Wow, this is good enough to publish!” then either a.) you’re being deliberately obtuse, or b.) you haven’t yet mastered your craft.

But maybe the uncanny valley is good enough for some genres. Beginning-to-end AI composition seems to have generated the most enthusiasm in repetitive, volume-focused genres like romance, erotica, and urban fantasy.

There is a reason for this. AI is incapable of true originality, but AI excels at pattern recognition. The above genres are heavily dependent on “tropes”.

To be blunt, much of the writing in these genres is not very good to begin with. (I’m talking about the human writing). Some writers may therefore decide that AI writing is “good enough” to compete in the marketplace. They may therefore be willing to trade quality for volume, especially if they’re focused on Amazon Kindle algorithms.

I urge you to resist this temptation.

Consider the source of the AI writing advice. The vast majority of people teaching these new whiz-bang AI writing shortcuts are frustrated writers. The indie writing space has long been filled with “gurus” who sell how-to guides, expensive courses, and even more expensive one-on-one coaching. The gurus opportunistically jump on the latest trends. AI writing is tailor-made for this cottage industry.

Almost none of these gurus are bestsellers themselves. But they all promise to make you a bestseller. That should tell you something.

If AI really could crank out twenty bestsellers a year, the gurus would be making plenty of money with their own AI-generated work, and guarding the details of their methods like state secrets.

But they’ve decided to build their business models on teaching you how to make millions from chatbot-written novels. How generous of them, right?

If I may present a metaphor here: I’m not opposed to texting. I send text messages every day. But some people (especially young people) want to take texting too far. Texting is fine for the quick communication of mundane information. (“I’m leaving now and I’ll be there in twenty minutes.”) Texting is horrible for important conversations that require nuance.

Likewise, AI is fine for proofreading, market research, and brainstorming. Use it to gather material for that next nonfiction book you’re planning. But if you let AI write your prose for you, your final product will never rise above the lowest common denominator…if that.

Why? Because a thousand other authors are cranking out books with that very same AI tool you’re using, which is underpinned by the very same software and database.

You will eventually regret this. Even if AI writing is “good enough” for the reverse-harem, billionaire, dragon shapeshifter romance subgenre this year, there’s always next year to think about. Next year, even more writers will be using that very same AI tool to churn out a novel over the weekend.

Anyone can purchase a subscription to Sudowrite or Novelcrafter. Only you have your brain, your experiences, your insights, and the skills you develop. Don’t discard that advantage because an AI writing guru has promised you a shortcut.

-ET