Using various phone apps, many parents now track the movements of their progeny from minute-to-minute. Some parents even track the movements of their adult children. One of my friends can tell you, at any minute of the day, where his two children are. My friend’s children are 26 and 30 years old.

I won’t mince words here. I find all of this geo-tracking to be a little neurotic, not to mention claustrophobic for those who must endure it.

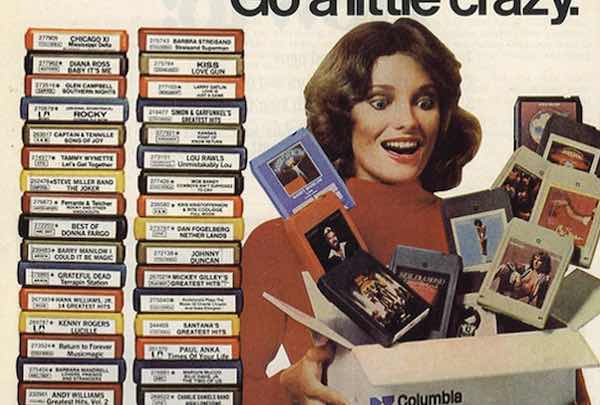

It was different for those of us who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, of course. At most hours of the day, our parents didn’t know exactly where we were. Oh, sure, they might have had some ideas, in the same way that I know Russia is to the east of me, and Argentina is to the far south. But don’t ask me to give you air travel coordinates. Suburban parents in the 1970s and 1980s relied on similar guesstimates regarding their children’s whereabouts.

During the summer months especially, we took full advantage of this location anonymity. The one thing most every Gen X kid had was a bike. And a bike was a license to travel distances your parents never would have approved of. Some of us planned long quests that would have been worthy of a JRR Tolkien novel like The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings.

The motivation for these unauthorized trips was often some kind of contraband: alcohol, cigarettes, or firecrackers. Sometimes it was just the thrill of seeing how far your ten speed would carry you in a single June or July morning.

Among adolescent boys, the motivations were often of an amorous inclination. I turned 13 in the summer of 1981. One of my neighborhood friends—I’ll call him Glen—had somehow initiated a running phone conversation with three girls who lived in a neighborhood far from where we lived. Somehow three of us—Glen, me, and one other boy—started talking to the girls, always via landline (the only communication option in those days) and always from Glen’s house.

The girls sounded both pretty and friendly. The girls said they wanted to meet us, but we would have to go to them. And so we planned a bicycle trip to their neighborhood.

Did we ask our parents’ permission? Of course not.

We set off on our bikes one morning around nine a.m. Being randy young males, we eagerly speculated about what might happen at our destination.

When we arrived nearly two hours later, however, the girls were nowhere to be found. Forty-five years after the fact, I’m not sure exactly what happened. We either had the wrong address, or we were duped. Disappointed, we rode back as a particularly hot afternoon settled in.

The lesson I learned from this was: if it seems too good to be true, a little too convenient, then it probably is too good to be true.

But that is the kind of life lesson that you can’t learn on a computer, and certainly not on social media. I’m grateful that I came of age when free-range childhood was still a thing. To grow up without geo-tracking was both a privilege and a blessing.

-ET