Krampus, Dickens, and what I saw on Christmas Eve, 1976

Merry Christmas, everyone!

Yes, I know this has been a lousy year. It’s almost over, though.

Christmas is generally a festive holiday, but there are some macabre Christmas traditions, too. And they didn’t necessarily begin with this very macabre year of 2020.

Consider, for example, the Dickens tale, A Christmas Carol. This is one of my holiday favorites. Who can forget the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, which reminds us of the Grim Reaper? Or, for that matter, Marley’s ghost?

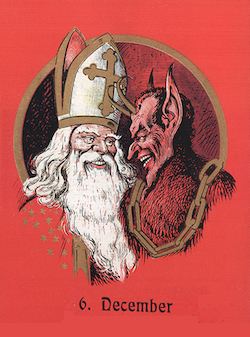

In some parts of Europe, Christmas includes the Krampus, a horned creature that incorporates both Christian and pre-Christian (pagan) traditions. In Germanic folklore, the Krampus works in conjunction with St. Nicholas, rewarding children who have been good, and punishing those who have been bad.

Let me tell you about something that happened to me on Christmas Eve many years ago…in 1976.

I was at my grandparents’ house in the suburbs of Cincinnati, Ohio. The family had just had our Christmas Eve dinner—Grandma’s turkey, stuffing, and mashed potatoes. (My grandmother also used to prepare a festive gelatin salad made with raspberry Jell-O, diced nuts, sliced carrots, and Cool Whip. (I realize that might not sound very tasty, but it was.))

Anyway, I had just left the table for a call of nature. This took me to a hallway in another part of the house.

There in the semidarkness of the hallway, I saw the shadow of a small, gnomish creature. It was right there, within lunging distance of me, cast on the wall.

I was startled—though not necessarily in mortal terror. Being eight years old in 1976, I ran back into the dining room, and told the adults.

There was something in the hall!

They accompanied me back to the hallway where I’d seen the unusual shadow. Needless to say, it was gone.

But there had been something there. I know there was.

My grandparents lived in that house for the rest of their lives. I was close to my grandparents, and visited them often, well into my adult years.

I never saw anything there resembling that gnome shadow figure again. Nor did I ever see any other other strange phenomena in the house.

But I know that something made a brief visit there on Christmas Eve, 1976.

A bad elf, maybe? I don’t know. But like I said, I saw something.