In the spring of 1981, my seventh-grade English teacher assigned our class “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”, a short story by James Thurber.

The eponymous lead character is a middle-age man who has gone into a trance in his day-to-day life. Walter Mitty is married, but there is no spark between him and his wife. (The Secret Life of Walter Mitty was published in 1939, before the advent of no-fault divorce.) The story’s sparse 2,000-odd words don’t tell us much more about the details of Mitty’s circumstances, but we can easily imagine him as a low- or mid-level administrative employee in an office somewhere.

To escape the dullness of his actual life, Walter Mitty retreats into various daydreams. He is alternately a US Navy hydroplane captain, a bomber pilot, and a brilliant surgeon. Mitty’s daydreams of a more glorious existence are inevitably interrupted when someone—often his wife—scolds him for zoning out.

I was twelve years old when I read this story for the first time. I remember enjoying some of the imagery of the story. But as a seventh-grader, I simply could not get my arms around the ennui and resignation that often accompanies middle age. I had not yet been on the planet for thirteen years. Everything was still new to me.

I recently reread Thurber’s story at the age of 57. What a difference 45 years can make, in the way one interprets a work of fiction.

I wouldn’t describe myself as a Walter Mitty. I don’t daydream about flying a navy hydroplane while I’m driving a car, as Mitty does. But at the age of 57, I do understand how a person can become disconnected from the larger world.

American society is forever fixated on the future, and that naturally tends toward a youth obsession. Once you reach a certain age, you tend to fall off society’s radar. People are much more interested in what younger folks are doing.

The flip side of that is that you, in turn, are much less interested in what most other people are talking about. This doesn’t necessarily lead to constant daydreaming. But it does lead to a sense that you are not as fully a part of this world as you once were.

This process might be unavoidable, and it might not be completely unhealthy, either, for aging individuals or for society at-large. Society would never change if the concerns of the same cohort of people forever dominated the zeitgeist. For the individual, gradually losing touch with the world—even in late middle age—might be viewed as an advance preparation for leaving the world entirely.

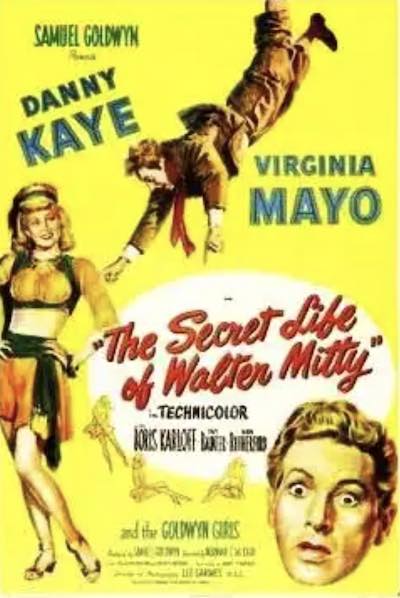

Anyway, “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” has apparently struck a chord with a lot of people since it was first published. The story was made into a movie in 1947, and then again at 2013.

I found “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” in the recent anthology, A Century of Fiction in The New Yorker: 1925-2025. You can also find the story on The New Yorker’s website.

-ET