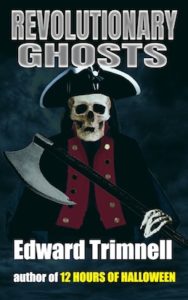

Get it on Amazon!

I stepped inside my house, and they were waiting for me.

I’m talking about my grandchildren, of course. Adam and Amy.

I may not always be popular at work. (No one in management, in any organization, is popular one hundred percent of the time.) But I’m popular with my grandkids.

“Grandpa!” they cried out. And then they came running. I didn’t even make it past the foyer.

Adam and Amy are nine and eleven, respectively. They are no longer small enough for me to swoop them up in my arms. I was knocked back a step when they executed their grandpa-tackle. They wrapped me in a joint hug.

I like being a grandfather. No—I love being a grandfather.

“You’re finally home,” Peggy said. She was walking in from the kitchen, wearing an apron. I could smell one of her meatloaves cooking.

“I got out as soon as I could,” I said.

Peggy looked down at Adam and Amy. She leaned over, her hands on her knees.

“Why don’t we let Grandpa change out of his work clothes? Then we’ll all have some meatloaf, and watch some TV.”

“Yay!” they shouted in unison, releasing me.

“Thanks, Peg,” I said. “I’ll be back in a jiffy.”

I watched Adam and Amy run off, back into the living room. I assumed they were playing video games.

Despite everything that had happened over the past week and a half, I was filled with a simple gratitude for my family, my station in life.

And no matter what had happened in the summer of 1976, the last forty years had been good ones.

I was especially grateful for Adam, whom we privately refer to as our “miracle child”. For Adam was almost taken from us.

But more about that a bit later.

The bedroom was mostly dark. A bit of light filtered in from the hallway, and through the shutters.

I considered turning on the overhead light. But no—that would be giving in to fear. I wasn’t going to go down that road. Not in my own house.

I removed my tie and draped it over one hook on the tie rack that hung behind the bedroom door.

I sat down on the bed, and kicked off my wingtips. I keep a pair of slippers beneath the bed.

I was slipping into the left slipper when I noticed something: The closet door was open—just a smidgen.

That feeling again. The feeling of not being alone, in a space that was supposed to be otherwise empty.

That feeling of being watched.

I slipped into the second slipper. I stood up from the bed. I walked over to the doorway of the bedroom. I could hear my grandchildren laughing at the other end of the house. Peggy’s meatloaf wafted down the hall.

I looked at the closet again. The little wedge of absolute blackness, between the door and the doorframe, was completely inscrutable.

But it was also taunting me. This is my house, I reminded myself. It is one thing to be jumpy in Dr. Beckman’s exam room. One thing to see things in my office, even.

One thing to see Banny in the parking garage of Covington Foods.

And who knew what might have been behind me on the road this evening?

But not here. Those forces will not be allowed to invade my home.

Rather than continuing out of the bedroom, I walked back to the closet. I ignored my fear, ignored the gooseflesh on my arms and neck.

I pulled open the closet door.

Nothing jumped out at me. Good.

There were clothes, both mine and Peggy’s, hanging on the shoulder-high closet rod. I pushed the clothes to one side, and then to the other, so that I could see the back wall of the closet.

If you’re there, I thought, show yourself now!

But which one of them was I silently speaking to?

In the summer of 1976 there had been far more than one.

At any rate, the closet was empty. I smelled the odor of fabric, the scent of mothballs.

I pushed the closet door shut until it clicked.

Peggy’s meatloaf was delicious, as usual. After dinner, the children preceded us into the living room. The television drew them like a tractor beam. Last year I splurged on a big, 85-inch Sony LED UltraHD television.

Extravagant, yes, I know. A far, far cry from the boxy Zeniths and RCAs of my childhood. But the children love the TV, both for watching and for playing video games.

Peggy and I were just walking into the living room, when Adam’s face lit up. He was scrolling through the on-screen channel guide.

“Hey, Grandpa!” he said. “Guess what’s on!”

I figured that it would be something involving either superheroes or spaceships. Both Adam and Amy are also ardent fans of those Harry Potter movies, based on the novels of that British author, JK-something-or-other. I’ve seen a couple of those films, and I couldn’t make heads or tales of them. But then, my grandparents would have found the original Star Trek equally incomprehensible. Each generation has its proprietary forms of entertainment, I suppose.

“What’s on, Adam?” I asked gamely.

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow!” he shouted. “You know: the Headless Horseman!”

I hoped against hope that my horror at Adam’s movie selection didn’t show.

Peg gave me a funny look.

“Are you all right, Steve?” she asked.

“I’m fine!” I said—though I wasn’t fine. There was nothing supernatural about Adam wanting to see a film version of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, of course. But how many coincidences did I need, in order to make me accept that something was up? How many coincidences would Dr. Beckman have needed?

I was vaguely aware of a movie rendition of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, made during the 1990s, or thereabouts. Johnny Depp starred in it. Or maybe that had been Sean Penn. (I haven’t really been current on my actors since the days when the average new Hollywood release featured some combination of Burt Reynolds, Sally Field, and Clint Eastwood.) I hadn’t seen the movie, of course. But I knew that it existed.

“It’s a cartoon!” Adam said. “By Disney!”

I was aware of such a cartoon. I had seen it as a child myself, when I was around Adam’s age. The cartoon was already at least ten years old then.

“Why, that’s a really old one, Adam,” I said. “Older than Grandpa!”

“It was made in nineteen forty-nine,” Adam provided. He had read about the cartoon on the online guide, obviously.

“Are you sure you’d want to watch something that old?”

“Some old movies are good!” Amy piped up. “Like The Wizard of Oz. Did you know that was made in nineteen thirty-nine?”

Where do kids nowadays accumulate so much information? I wondered. On the Internet, no doubt.

“It might be a bit too intense for you,” I tried. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow might give you nightmares.”

I was hiding behind my grandchildren, of course. I was actually afraid that the old cartoon might give me nightmares—or at least contribute to them. (And that is, incidentally, exactly what happened.)

Then Peggy intervened. “It’s a Disney animated feature made in nineteen forty-nine, Steve. I think it will be all right. Have you seen some of the things kids see on the Internet nowadays? That old cartoon will be mild by comparison. Heck, I saw it myself when I was about their age. I think everyone did, at one time or another. It’s a classic.”

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow—a classic? I didn’t think so. But I didn’t argue my point any further.

I sat through The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Luckily, it’s a short one: about an hour, with commercial breaks.

At several moments in the movie, I found myself flinching at the animated version of the Headless Horseman.

And when I flinched, I noticed Peggy noticing me. From her perspective, my behavior must have seemed odd.

The creators who conceived and made that cartoon seventy years ago had not intended it to be shocking, of course. They had, rather, produced it as light children’s entertainment.

But we can safely assume that none of them had ever encountered the real Headless Horseman. To them, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow was just that…a legend.