My bedroom was a small, cramped affair, very typical of secondary bedrooms in postwar tract homes. There was barely enough room for a bed, a desk, a bureau, and a chest of drawers. The one selling point of the bedroom was the window over the bed. It afforded me a view of the big maple tree in the front yard, when I felt like looking at it.

I lay down on my bed and opened Spooky American Tales. I briefly considered reading about the Nevada silver mine or the Confederate cemetery in Georgia.

Instead I flipped back to page 84, to Harry Bailey’s article about the Headless Horseman.

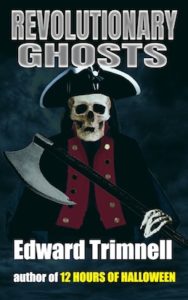

After the opening paragraphs, Harry Bailey explained the historical background behind the legend of the Headless Horseman. While most everyone knew that the Headless Horseman was associated with the American Revolution, not everyone knew the particulars:

“Is the Headless Horseman a mere tale—a figment of fevered imaginations? Or is there some truth in the legend? Did the ghastly Horseman truly exist?

“And more to the point of our present concerns: Does the Horseman exist even now?

“I’ll leave those final judgments to you, my friends.

“What is known for certain is that on October 28, 1776, around three thousand troops of the Continental Army met British and Hessian elements near White Plains, New York, on the field of battle.

“This engagement is known in historical record as the Battle of White Plains. The Continentals were outnumbered nearly two to one. George Washington’s boys retreated, but not before they had inflicted an equal number of casualties on their British and Hessian enemies…”

By this point in my educational career, I had taken several American history courses. I knew who the Hessians were.

The Hessians were often referred to as mercenaries, and there was an element of truth in that. But they weren’t mercenaries, exactly, in the modern usage of that word.

In the 1700s, the land now known as Germany was still the Holy Roman Empire. It consisted of many small, semiautonomous states. In these pre-democratic times, the German states were ruled by princes.

Many of these states had standing professional armies, elite by the standards of the day. The German princes would sometimes lease out their armies to other European powers in order to replenish their royal coffers.

When the American Revolution began, the British government resorted to leased German troops to supplement the overburdened British military presence in North America. Most of the German troops who fought in the American Revolutionary War on the British side came from two German states: Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Hanau. The Americans would remember them all as Hessians.

The Hessians had a reputation for brutality. It was said that no Continental soldier wanted to be taken prisoner by the German troops. The Continentals loathed and feared the Hessians even more than the British redcoats.

I supposed that Harry Bailey would have known more about the Hessians than I did, from my basic public school history courses. But Harry Bailey wasn’t writing an article for a history magazine. The readers of Spooky American Tales would be more interested in the ghostly details:

“That much, my dear readers, is indisputable historical record. Journey to the town of White Plains, New York, today, and you will find monuments that commemorate the battle.

But here is where history takes a decidedly macabre turn, and where believers part ranks with the skeptics. For according to the old legends, one of the enemy dead at the Battle of White Plains would become that hideous ghoul—the Headless Horseman.

A lone Hessian artillery officer was struck, in the thick of battle, by a Continental cannonball. Horrific as it may be to imagine, that American cannonball struck the unlucky Hessian square in the head, thereby decapitating him.

What an affront, from the perspective of a proud German military man! To have one’s life taken and one’s body mutilated in such a way!

So great was the rage of the dead Hessian, that he would not rest in his grave! He rose from his eternal sleep to take revenge on the young American republic after the conclusion of the American Revolution.

This is the gist of Washington Irving’s 1820 short story, ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’. The tale is set in the rural New York village of Sleepy Hollow, around the year 1790.

But we have reason to believe that ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ was not the last chapter in the story of the Headless Horseman. For according to some eyewitness accounts, that fiendish ghoul has returned again from the depths of hell.

Read on, my friends, for the details!”

Lying there on my bed reading, I rolled my eyes at Harry Bailey’s florid prose. He was really laying it on thick. But then, I supposed, that was what the readers of a magazine called Spooky American Tales would require.

Then I noticed that the hairs on my arms were standing on end.

My gooseflesh hadn’t been caused by the article in Spooky American Tales—at least, I didn’t think so. I hadn’t yet bought into the notion that the legend of the Headless Horseman might be anything more than an old folktale.

Nor was the temperature in my bedroom excessively cold. Three years ago, my parents had invested in a central air conditioning system for the house. They used the air conditioning, but sparingly. It sometimes seemed as if they were afraid that they might break the air conditioning unit if they kept the temperature in the house below 75°F. With the door closed, it was downright stuffy in my bedroom.

I had an unwanted awareness of that bedroom door, and what might be on the other side of it.

The shape I had seen in the hallway.

Then I told myself that I was being foolish.

It was a bright, sunny June day. The walls were thin, and the door of my bedroom was thin. I could hear the muffled murmurs of the television in the living room.

It wasn’t as if I was alone in some haunted house from Gothic literature. I was lying atop my own bed, in my own bedroom, in the house where I’d grown up. My parents—both of them—were only a few yards away.

There is nothing out there in the hall, I affirmed.

With that affirmation in mind, I continued reading.