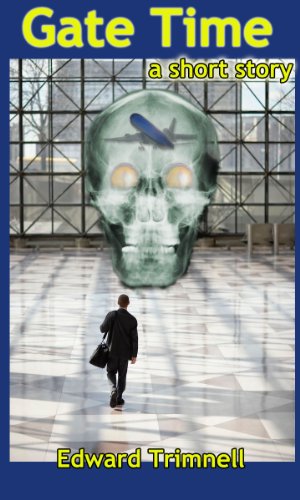

A software salesperson discovers that he can commune with the dead at airports.

Josh Gardner spent a lot of time in airports. That territory came with a job in software sales. As a sales rep for EntroSoft, Josh was responsible for three dozen corporate accounts in eleven states. Every week it was the same routine: airports and hotel rooms and rental cars. But EntroSoft’s commission structure was decent; and Josh preferred living out of a suitcase to being stuck in an office all day, like so many other working schmucks. It was still work—but work with a certain degree of freedom.

Not that there was no monotony involved. Flying often meant hours stranded in an airport, waiting for a connecting flight. When the flights lined up poorly, a layover could last as long as three hours.

The key to staying sane during a long layover was knowing how to entertain yourself. He had that problem solved. Airports were a great place for people-watching. Josh was in his early thirties and still single, so most of his people-watching involved people of the female persuasion. (And women always dressed to the nines when they flew.) But airports offered human novelties of every gender, age, and creed: foreigners babbling in incomprehensible languages, oddballs peddling flowers and handing out pamphlets, and so many businesspersons like himself.

Josh was not shy about talking to strangers (how could you be, and survive in sales?); and he occasionally struck up a conversation with someone who might prove influential in the next deal, or even the next job. It could never hurt to pad your Rolodex.

So Josh was not particularly taken aback when the man in the navy uniform spoke to him out of the blue. The two of them were sitting across from each other in a little island of seats in the middle of O’Hare’s Concourse B. Josh was just about to stand up and head to his gate when the sailor asked:

“Hey buddy, can I bum a smoke?”

The sailor was wearing a dark blue uniform and he had two chevrons on his sleeve. What did that make him? A sergeant? A corporal? Josh had never been in the military and he had no idea if the navy even had sergeants and corporals. Probably not—but no matter. The navy man must have noticed the half-full pack of Marlboros in Josh’s front shirt pocket.

Josh had started smoking in college, and he had continued the habit off and on since then. He was currently in one of his “on” phases; but climbing back onto the nonsmokers’ wagon was an item on his immediate to-do list.

“As a matter of fact,” Josh said, “You can have the whole pack. I’m trying to quit.” The sailor’s eyes lit up. He was a good ten years younger than Josh, maybe twenty-two or twenty-three.

“That’d be swell. Thanks.”

“Well, you’ve got it.” Josh stood up and pulled the pack of cigarettes from his pocket. He tossed them to the navy man.

“You’re a—” Josh gestured to the chevrons on the navy man’s sleeve.

“Seaman Second Class.” The navy man smiled. He apparently didn’t mind getting questions from a curious civilian.

Josh wasn’t done. “You’ve been in the Persian Gulf? Near Afghanistan? Iraq?”

The sailor shook his head. “Naw. I’ve been to Liverpool, Bristol. And Murmansk. That’s in Russia.”

“Hmm.”

“Say, let me pay you for the smokes.” The sailor began digging in his pockets.

“No. No. That’s not necessary.”

“I insist. There’s the better part of a pack here.”

The sailor withdrew a silvery coin from his pants pocket. Josh could tell from its size that it was a quarter. The sailor made a fist and placed the quarter on his thumbnail. He launched it with his thumb and it came rolling through the air at Josh.

That’s a cool trick, Josh thought, as the quarter spun end over end toward his nose. He would lose face if he failed to catch it, so he shot out his hand and caught the coin in midair. He pocketed the quarter without looking at it, thinking: Cool trick, but a quarter for a nearly full pack of cigarettes? Accepting the pack gratis would have been a bit less tacky.

“Well, you have a good trip.” Josh lifted his briefcase and carry-on bag.

“Same to ya, buddy.”

As he departed, Josh had a final thought: Hopefully the sailor remembered that smoking was illegal in U.S. airports. There were probably no such restrictions in Russia.

By the time Josh arrived at his gate, the cattle call to board the plane had already begun. As Josh stood in line he became aware of the weight of the sailor’s quarter in his pocket.

He removed it and noticed that it did feel heavier than the typical quarter. He rubbed the coin between his thumb and forefinger. The heads side of the quarter bore the usual bust of George Washington. Turning it over, there was the standard eagle design on the tails side.

Then he noticed the date on the quarter: This coin was minted in 1939. Josh had dabbled in coin collecting as a kid, and he remembered that quarters minted before 1964 were 90% silver. It would therefore be worth a heck of a lot more than its face value of twenty-five cents. Not a fortune, mind you: but at least three to five bucks.

So the sailor had more than paid for his pack of cigarettes. Did he pass the antique coin on purpose? That would be an odd bit of irony for a kid in the navy. But how else could you explain it? How could a silver quarter from 1939 be in circulation after so many years?

Josh let the airline employee take his boarding pass and wish him a pleasant flight. His mind was churning. There was more to this than met the eye. He stowed his bags in the overhead compartment aboard the plane and took his seat at the aisle.

The sailor had claimed to have visited Bristol, Liverpool, and Murmansk, Russia. The U.S. Navy didn’t send many vessels to Russia. Not after the Cold War and all that. And what would a navy man be doing in England? All the action was in the Middle East. There was no war in England or Russia.

Josh smiled. But there had been, about sixty years ago. The sailor had described a typical tour of duty in the European Theater during the Second World War. And then he handed over a silver quarter minted in 1939.

The “sailor” had no doubt been an actor of some sort. Josh had once seen a CNN segment about a historical society somewhere that sent its members out into public clad in various period dress. The faux navy man with a hankering for cigarettes had been part of a similar skit.

Josh leaned back in his seat as the plane lifted off the runway. That guy had me going, he thought. He was pretty good—played his routine straight all the way.

Josh respected the actor’s technique. (Now that guy ought to be in sales.) There was no harm done. In fact, it had been a rather profitable exchange for Josh. He was back on the nonsmoking bandwagon again, and he could hawk the silver quarter on Ebay over the upcoming weekend.

The plane took Josh to Pittsburgh, where one of the big banks that he called on had its headquarters. That evening he had dinner with his contact at the bank: a thin, pallid accountant type named Gordon Frye. They ate at one of the best steakhouses in Pittsburgh. Frye wasn’t exactly loaded with interesting topics of conversation, and Josh soon grew tired of talking about banking.

“Gordon, do you know anything about old coins?” Josh asked.

Self-satisfied pleasure spread across Gordon’s face, and Josh knew that he had hit pay dirt.

“I’ve been collecting coins for thirty years,” Gordon said. “Ever since I was a kid.”

“Awesome.” Josh told Gordon about the sailor he had met at O’Hare. Then he removed the quarter from his pocket and handed it to the banker.

Gordon held the coin by its edges between his thumb and forefinger. He whistled as he appraised it against the overhead light. “Holy smokes, Josh. Some guy just gave you this for a pack of cigarettes?”

“Yep. The navy guy. And it wasn’t even a full pack. What’s up, Gordon, is this quarter really worth something? Based on the amount of silver here, I was thinking like three or four bucks.”

Gordon shook his head. “It’s more than just the silver, Josh. Look at the condition. This coin is practically uncirculated.”

Josh took a bite of his dinner roll. “Well, how about that? What do you think its worth?”

Gordon frowned. “Difficult to say for sure without a numismatic guide. The prices of historical coins fluctuate all the time. I mean: don’t get me wrong—you’re not going to retire on this thing. But you might get a hundred bucks or so from the right buyer”

“A hundred bucks? Wow!”

Gordon laid the quarter on a clean linen napkin and scooted it back across the table to Josh. “You’d better wrap this up in a non-abrasive fabric of some sort until you get it home. Then take it to a coin dealer for an appraisal. You’ve definitely got something here.”

Josh finished off his dinner roll. “I can’t believe this.”

“Neither can I. Remind me to always take a pack of cigarettes with me when I fly.”

Josh spent the night in Pittsburgh. After Gordon’s appraisal of the coin, he had no intention of leaving it in his pocket for the rest of the trip. Before turning off the lights in his hotel room that night, he wrapped the quarter up in one of his dress socks and placed it deep inside his carry-on bag.

His next destination was San Francisco. This leg of the trip was a long one, with a layover in the Midwest. Josh found himself stranded for two hours in a tiny airport in one of the Great Plains states. There was only one concourse in the airport. The airport’s lone restaurant was a small food court-style vendor. The restaurant served pizza and oversized pretzels from a glass case equipped with heat lamps.

After forcing down a slice of the heat-lamped pizza, Josh took a window seat in the concourse near his gate. Beyond the glass the land was an endless, undulating sea of grass. The middle of nowhere, Josh thought. His stomach was roiling with the greasy pizza. He couldn’t wait to board the plane for San Francisco. Tonight he would treat himself to dinner at one of the city’s best seafood restaurants. Or maybe he would go for Chinese. After all, he had his expense account.

Josh looked in the direction of his gate to see if the airline employees had placed the sign for his flight above the ticketing counter yet. He had not noticed the woman in the long dress and bonnet sit down two seats to his left, but here she was now. The woman might have been in her late twenties or early thirties. Hard to tell for sure.

Whatever her age, her dress and bonnet were straight out of the nineteenth century. She looked like she should have been at the front of a Conestoga wagon in that outfit.

Josh appraised the woman as pretty if a little plain, if you could get past her complexion. She had a nasty case of acne. And her hair—light brown as far as Josh could see—was mostly obscured by that ridiculous bonnet.

Josh cleared his throat before speaking.

“So you folks are doing all the airports, huh? I fly a lot, and I met one of your colleagues in Chicago. I love the idea: period costumes to encourage more awareness of history. And why not in airports? These places are full of people with lots of time on their hands.”

Josh couldn’t help wondering if this exchange would lead to another silver coin. If a World War II-era sailor gave out 1939 quarters, then what would a woman in nineteenth-century garb be handing out? Morgan silver dollars? It might not be too much to hope for. She didn’t look like the type to smoke. Perhaps he would offer her a stick of gum and see where things went from there.

However, this woman wasn’t as talkative as the sailor had been. She did not speak; the only response Josh got was a flinty stare. Josh looked more closely at the woman’s face. Her acne was much worse than it had originally seemed to be.

“Hey, sorry,” Josh said. “Did I say something wrong? I mean, I figure if you dress up like that it’s because you want people to notice.”

No answer. The woman’s lips tightened. She was practically trembling with some strong emotion: maybe anger, maybe sadness, maybe both. Talking to her had definitely been the wrong move.

Then the overhead intercom interrupted their one-way conversation:

“American Airlines Flight 2433 will be boarding for San Francisco in twenty minutes.”

“Hey,” Josh said. “That’s my flight. Sorry for whatever I said that offended you.” He stood and hoisted his bags. “You try to have a better day. See you around.”

Josh hurried off, glad to be away from the woman’s withering stare. It wasn’t often that Josh’s gift of gab received a negative reaction. Most people returned his friendliness in kind. But that woman had obviously been a head case.

Well, you just couldn’t take an encounter like that personally. You had to write off the occasional oddball.

At the gate, Josh found a seat next to a middle-aged woman in a business suit. She glanced up from her USA Today as Josh sat down. She looked a lot friendlier than the woman in the bonnet.

“You can’t wait to get out of the cornfields, either, huh?” Josh asked.

She folded her paper across her lap. “Actually, I’m from the cornfields. I live around here.”

Josh shook his head. “This seems to be my day for putting my foot in my mouth. No offense intended.”

“None taken. For what it’s worth, this part of the country can get a little boring from time to time. Especially in the winter.”

“Well, your local historical society is trying to liven things up. I just saw a woman dressed like someone out of the 1800s. But she didn’t want to talk to me. And I didn’t even make any remarks about cornfields.”

“That’s odd,” Josh’s fellow traveler stifled a yawn. “The only historical thing around here was Simpsonville. It’s not the sort of history that anyone would particularly want to celebrate, though.”

“Why’s that?”

“Well, there was a pioneer settlement right around here in the 1850s. Or it might have been the 1860s. I don’t remember exactly. Anyway, the whole town died in a smallpox outbreak. Tragic stuff, as long ago as it was.”

“Jeez. That’s awful.” Josh felt his Blackberry buzzing in his pants pocket—probably another message from his office. “Well, I guess life was different back then, right? With all those diseases that could kill you at any moment.”

The woman lifted her USA Today and began reading an article about a new Iranian missile program. “Yes. I for one am glad to be living in a safer time.”

Josh closed a big contract in San Francisco; next month’s commission check from EntroSoft would be a nice one. He left San Francisco the following night on a redeye bound for Detroit. Overnight flights were no problem for Josh: one on-board cocktail and he was out like a light.

He landed at Detroit Metro Airport around five a.m. He was groggy, hungry, and his mouth had that first-thing-in-the-morning sour taste. There were few people in the concourse where he deplaned; it was still several hours before the morning rush. Nevertheless, at least a few of the airport restaurants would likely be open. A plate of pancakes or bacon and eggs would placate his growling stomach.

Josh stepped into the first men’s room he found. At this hour he had its five stalls, six urinals, and four washbasins to himself. At seven-thirty this place would be standing room only.

He pulled his toiletry kit from his carry-on bag and began brushing his teeth at one of the washbasins. His mouth was full of toothpaste foam when he heard a male voice speaking in a foreign language.

Whatever the language was, it wasn’t French, Spanish, or German. Those languages Josh could recognize, even though he didn’t speak them. The language was something Middle Eastern. Arabic maybe? And where was the voice coming from? The restroom had been empty when he walked in.

Josh rinsed out his mouth and tried to pinpoint the source of the talking. The voice seemed to be coming from inside one of the stalls at the far end of the restroom. Probably some guy talking on his cell phone while he sat on the crapper.

Well, whatever he was talking about, he was obviously getting more upset by the second. Josh didn’t need to understand the language to decipher the tone. The guy was on the verge of hysteria.

Josh returned his toothpaste and brush to his toiletry bag and zipped it closed. The frantic voice continued yammering away, its owner unseen. Could you hold it down, buddy, Josh wanted to shout. I’m still getting fully awake here.

Josh bent down to pick up his bags and suddenly the voice was clearer—and closer.

He snapped upright and stared into the face of a bearded man with dark eyes and an olive complexion. The man was dressed in a dishdasha: the plain body-length robe so common in the Middle East. This man’s dishdasha had originally been white. Now most of it was soaked red. Blood was also spattered in the man’s beard and hair.

The man spoke directly to Josh in that strange foreign tongue, as if he fully expected Josh to answer in the same language. Josh felt his own words choked in his throat when the man lifted a hand. Two of the hand’s fingers had been freshly severed.

Josh backed away, drawing in breath as the wounded man reached out for him with his mutilated hand. He tripped on the strap of his own travel bag and fell backward. His tailbone smarted as he sat down hard on the cold tile.

Josh was still lying on the floor when he saw the hole in the man’s abdomen. It was about the size of a softball, though ragged and apparently burned around the edges. The hole was more than just a deep wound: it went clear through him. Josh could see the far wall of the bathroom through the open space where the rest of the guy’s body should have been.

Despite the feeling that he was going to pass out at any second, Josh used his hands to push himself backward. His head struck the wall underneath the automatic hand dryer. He was oblivious to the pain; all of his will was focused on getting away from this man with the impossible injuries.

The stranger gave Josh another spate of the guttural talk, and then abruptly dismissed him. He turned toward the open doorway to the concourse and exited the restroom. Josh got a brief glimpse of the hole from the other direction: no, there was no doubt about it—there was a hole right through the center of his body.

Although Josh’s stomach was all but empty, he felt his gorge rising. He scrambled to his feet and just made it into one of the stalls before the retching fit began. It was like the dry heaves that he sometimes got after a night of drinking too much. His stomach was convulsing but nothing much was coming out.

When it was over, Josh stood before the mirror above the washbasins and splashed water on his face. He was trembling. He didn’t know how to process what had just happened. He didn’t even know how to approach the task of processing it. Josh was no medical expert; but he was pretty sure that he had just been accosted by a man with a fatal abdominal wound, not to mention a few missing fingers.

No one could walk around and talk with a hole like that in him.

No one could even be alive with a hole like that in him.

So where does that leave us?

He gathered up his things and walked out into the concourse. There was no sign of the stranger with the blasted-out abdomen. Nor was there any indication that anyone else had seen him. People weren’t clustered together asking each other for explanations. There was no buzz of speculation among strangers, nor was there the unearthly silence that often accompanies a bizarre event. The few people who Josh could see in the concourse appeared sleepy and bored, nothing more.

A television monitor was mounted about two feet below the ceiling in the waiting area of one of the gates. It was tuned to the international version of CNN—standard fare for the airport crowd. A female newscaster with a British accent narrated footage of what appeared to be another Third World disaster scene. Josh could make out the twisted, smoking wreckage of an automobile chassis, and rows of hastily covered bodies across the screen. The film footage was grainy, and a string of cursive script ran like a ticker at the bottom of the broadcast images. Josh recognized the writing as Arabic script, the kind used to represent various languages in the Middle East.

“Authorities in Karachi, Pakistan report that at least twenty people were killed today when a car bomb exploded in a crowded suburban market. Police are searching for local militants who have claimed responsibility…”

As Josh stood in the middle of the concourse, the lightheaded, near fainting feeling returned again. Was it too farfetched—the idea that one of the Karachi bomb victims had just angrily addressed him in the restroom?

It was plenty farfetched; but so was the idea of a living, breathing man walking around with a hole like that in the center of his body.

Josh shook his head. If anyone was watching him, they no doubt thought that he was crazy, shaking his head while standing alone in the middle of the concourse.

Got to put this in a box for now, Josh thought, and dissect it later when there’s more time. Maybe I am seeing things. I’ve been burning the candle at both ends lately. Could be too much travel, too many late nights and early mornings. A schedule like mine has a cumulative effect on the mind and the body.

He didn’t have time to sort through this now. He was no longer in any mood for breakfast; but he had an early morning appointment in Ann Arbor, nearly an hour away from the airport. It was a fair hike to the Hertz car rental office; and Detroit Metro’s human traffic was picking up as the morning wore on.

So he purged his mind of what he had just seen in the men’s room, and its possible connection to the events on the television monitor. Instead he focused on the sales presentation he had to deliver in less than two hours. Or at least he tried to.

Details: focus on the details. What about his PowerPoint slides? Did he need to tweak them on his laptop before the meeting? Now there was something to distract him from what he had just seen. He pictured the bullet points in his PowerPoint presentation, and that steadied him.

Now Josh thought not of dead men who walked and talked, but of the faces of the men and women who be in this morning’s meeting. He anticipated their questions and how he would answer them. Word-for-word, he ran through various scenarios that might arise during the meeting.

As Josh set off for the rental car office, CNN continued its account of the carbombing in Pakistan.

He was finally home for the weekend. Josh usually preferred to be out on the town on a Friday night; but this week he was taking it easy. He went to bed shortly after ten, and to his surprise, sleep came easily.

He awoke a little after two in the morning, thirsty. His thirst quenched by the filtered water tap in his refrigerator, he was seized by another feeling: the sense that someone was watching him.

There was a skylight in his kitchen; it was one of the features that had attracted him to this condominium. Josh stared up through the window at a slice of moon that was partially obscured by clouds. Then he shivered and looked away. Would the face of the blast victim from the men’s room appear there at any second, jabbering away at him in Urdu?

There was a grinding and cracking sound as the building settled. Josh set his tumbler of water down on the counter so hard that he wondered if he had cracked the glass. He was becoming jumpy.

Since he was awake anyway, there was an open loop that he needed to close. His computer monitor sat atop the desk that he kept in a corner of the living room. He sat down before the monitor and grabbed the computer’s mouse. The monitor stirred to life with a static pop and a burst of fluorescent glow.

He typed the word “smallpox” into the text field on Google’s homepage and hit the search button. A long list of hyperlinks filled the screen. Josh randomly selected the third one down from the top. He was taken to the Centers for Disease Control’s page on this particular torment of nature.

The CDC site stated that smallpox had been virtually eradicated by 1980, though various terrorist groups were burning the midnight oil in the hope of adding a new chapter to the disease’s long history. The last major outbreak of smallpox had occurred in Somalia in 1977.

Josh found a hyperlink nested in the CDC’s text that took him to a gallery of old photographs that depicted past smallpox victims. Most of the images were from the developing world, since the disease had become rare in North America and Europe in the early twentieth century.

One photo showed a small boy lying on a straw mat, his face an eruption of smallpox pustules. Although Josh couldn’t be sure, this unfortunate child’s affliction looked nearly identical to the disfiguration suffered by the woman in the airport in Nebraska. And he had mistaken her skin problem for a bad case of acne.

Then he executed a search for “Simpsonville, Nebraska.” All he came up with was a short Wikipedia entry. Unlike the disease that had wiped the community out, Simpsonville, Nebraska hadn’t lasted long enough to leave a lengthy history:

“Simpsonville, Nebraska was settled in 1864 by ten families who migrated to the area in order to claim undeveloped land in accordance with the 1862 Homestead Act. After surviving two harsh Nebraska winters, the settlers of Simpsonville were struck by disaster in the spring of 1866, when an outbreak of hemorrhagic smallpox killed nearly ninety percent of the community.”

Josh closed the browser and pushed his chair away from the computer. He didn’t need to know any more about the history of epidemics in nineteenth-century America, nor about Simpsonville.

His gaze fell upon the closed door of the closet in the front foyer. Had he just heard something shift in there? The Pakistani man maybe? Or perhaps the woman in the bonnet, angry because she had died of smallpox before her time? Or was it the sailor coming back to collect his quarter, no longer in a friendly mood?

Josh stood up and strode over to the closet door. He paused before it. Then he placed his hand around the doorknob. One. Two. Three.

He yanked the door open, ready for anything.

But he saw only his winter coats and other assorted articles of clothing hung up on hangers. There was no apparition, no visitor from beyond the grave reaching out for him with spectral limbs. He reached inside the closet and flicked on the light switch. Still nothing. Then he performed one final test. He pushed the hangers first to one side and then the other, so that he could see all the way to the back of the enclosure.

All clear. There was nothing in his closet but clothing and the faint smell of mothballs. And even though he had needed to positively verify the situation, somehow he had known that the closet would be empty.

His condominium might be eerie at two o’clock in the morning; but any shadowy place would seem eerie after this past week. The important point was that they weren’t likely to turn up here. There were no spooks in his condo. His new companions would only show themselves in airports. That seemed to be the pattern.

He had gone back and forth with himself about the nature of these visitors. If indeed they were ghosts, they were different from the wispy presences of childhood campfire stories. Would an ethereal spirit pay in cash for a pack of cigarettes?

But the sailor’s quarter could not explain away the massive hole in the Pakistani man. Even the irrational things of this world were subject to a certain type of deductive reasoning. Josh had now gotten his arms around the fact that he was seeing ghosts. These were ghosts with material aspects to them, but ghosts nonetheless.

What Josh couldn’t say for sure was why they appeared in airports. He had an idea, though: airports were big, anonymous dens of humanity where anyone could fit in—maybe even the occasional restless soul. Of course this wouldn’t be true for a traumatic case like the bombing victim he’d met in Detroit. Nevertheless, the sailor and the woman in the bonnet had seemed almost normal—they could practically pass for real live humans, if that was their objective.

Maybe what the dead wanted was not to thump around in attics, or manifest themselves in ways that were guaranteed to terrify the living. Perhaps some of them wanted to commune with the living like they used to do when they were still alive themselves.

And what better place for that than in an airport? In an airport the slightly unusual could pass for normal, because you never knew where someone was from, or where they might be going. In an airport you looked at everyone, but you didn’t look at anyone too closely. What better place for the dead to blend in with the living?

Josh returned to bed although he knew that there would be no more sleep tonight. The fact that his condo was free of any abnormal presences brought little comfort. He would have to fly again on Monday.

He was just a normal kid, about nine or ten years old. And he was reading a Spiderman comic book. Nothing unusual about that. He was wearing shorts and a tee shirt and sitting at the gate in the row of seats across from Josh.

Nothing unusual at all.

Josh was waiting for a plane that would take him to Milwaukee. Here in Memphis it was raining buckets. Any minute one of the airline employees at the gate counter would speak into the microphone and announce that the flight was delayed. Josh was sure of it: a heavy rain could disrupt flight schedules as quickly as a blizzard or a nuclear war.

He looked at the boy again. His face was obscured by the Spiderman comic. On the cover of the comic, the Green Goblin had Spiderman in a horrible predicament. That was half the fun of Spiderman, of course. The Wallcrawler would no doubt extricate himself from the situation over the course of the comic book’s several dozen pages.

The boy’s mother, who was sitting beside him, gave her son a contented glance. A proud mother. The mother drew Josh’s attention, and not just because she was a fairly attractive female who was reasonably close to his own age. There was something odd about her attire. Mom’s skirt was short—way shorter than your average suburban hausfrau would usually wear. And her hair reminded Josh of a beehive or something. It was piled high atop her head, as if held in place with a half a bottle of hairspray.

That’s a new style. Josh thought.

No—that was an old style. Josh had seen old photos of women with beehive hairdos and miniskirts. The boy’s mother was apparently trying to affect a retro eighties look.

No—more retro than that. Josh had been in grade school during the 1980s; his babysitters and female teachers had never dressed like that.

Then he took another look at the Spiderman comic. The price printed on the cover was 12¢. How long had it been since comic books had sold for twelve cents? Twenty years? Thirty years? Maybe even forty years?

Oh my….Not another one of them…No: this time it was a pair of them.

But these two were different. They lacked the eagerness to engage the living that characterized the sailor. Nor did they have the brooding melancholy of the woman in the bonnet. And they were, of course, nothing like the carbomb victim.

The woman caught Josh staring at her and arched her eyebrows ever so slightly—like any happily married woman would do when an unknown man was giving her the eye. And the boy was still ignoring Josh completely; he was only interested in the comic.

That’s what’s different about these two, Josh thought. They aren’t doing the ghostly thing, they’re doing the human thing. It was as if they really were waiting for an airplane.

And perhaps they were. Josh noticed the other passengers waiting at the gate: A girl of nineteen or so was dressed in faded blue jeans and a tee shirt bearing a peace sign. Her boyfriend wore long hair, grungy jeans, and a leather vest with fringes. The other passengers were similarly retro: bouffant hairdos, horn-rimmed glasses, miniskirts, and absurdly wide belts. A thirtysomething businessman was clad in a three-piece charcoal grey suit and a suede fedora hat. No man under the age of seventy would be caught dead in a hat like that today.

Like the woman and her son, the other passengers were ignoring Josh, waiting for the plane.

Maybe these aren’t ghosts, Josh speculated. Maybe they really are alive, only not alive in the present. (Well, some of them would be—the boy with the Spiderman comic would be in his early fifties now.) But that’s not the point. My involuntary communications with the dead have now opened me up to events of the past as well as people of the past.

This would mean that the plane Josh and the others were waiting for was bound for Milwaukee, but not the Milwaukee he was expecting. And Josh became suddenly convinced that if he boarded the plane for Milwaukee he would cross a line that could not be crossed again. He would step into the airport in Milwaukee and it would be 1966 or 1968, ten or twelve years before he was even born. In this version of Milwaukee, Jimmy Hendrix and the Beatles would still be making the Top 40. Outside the airport, the parking lot would be filled with antique cars made new again, every one of them a gas-guzzling highway schooner with tailfins. And beyond the airport he would find an entirely different country with different problems, where no one had ever heard of AIDS, Osama bin Laden, or computer viruses. Newsstands would ply headlines about the war in the jungles of Southeast Asia instead of the wars in the Middle East.

Josh shivered. If he boarded this plane he would be lost forever in a place where he did not exist—should not exist.

“We will begin boarding Flight 791 for Milwaukee in about five minutes,” the airline employee announced over the intercom.

Josh hastily pulled his boarding pass out of his shirt pocket. His boarding pass entitled him to a ride on Flight 850. It was the same airline, same departure time, but a different flight number.

And no doubt a different year as well. Josh supposed that there had once been a Flight 791 from Memphis to Milwaukee, and he was now sitting with the passengers who had taken it one day forty years ago.

It was almost time to board the plane. He could not linger any longer. He stood abruptly and hurried into the general traffic of the terminal, not daring to look back at the gate for Flight 791 slash 850.

Josh headed past the security check—back the way he had come. He found himself in one of the main concourses of the Memphis airport. The scenery around him was distinctly twenty-first century; this realization brought him a modicum of relief.

It was late afternoon—one of the worst times to be caught in an airport—and the place was packed like a football stadium. He stared into the crowd and caught glimpses of the people passing by: a middle-aged man who looked due for a heart attack, a slender teenage girl who might perish in an automobile accident this very day. A mother with a young child in tow—

Josh recalled a statistic that he had gleaned from a documentary about population trends. Each day about 150,000 people die. One hundred and fifty thousand men, women, and children. But the population of the earth increases nonetheless, because each day there are also about 350,000 births. The constant churn of lives and souls.

All these people in the airport with him: how many of them were living, and how many were dead?

Josh turned around and a man in a bowler hat and a three-piece suit was staring straight at him. The staring man’s outfit was complete with a waistcoat and a pocket watch. He carried a walking stick. Josh guessed that this one was from the late nineteenth century, an era of horses and buggies, a time when a simple infection could mean death.

He and Josh faced each other silently, until the former spoke.

“I know, you see me,” he told Josh. “But you’re not supposed to be able to see me. You shouldn’t be able to see any of us.”

Josh backed away. There were angry grunts as he went against the traffic and people bumped into him.

“It’s dangerous,” the man in the bowler hat continued. “There are good ones in here as well as bad ones.”

As Josh whirled around and broke into a run he heard the man in the bowler hat say:

“Stay out of here if you can.”

Two weeks later Josh was back in an airport again. He had taken some heat from his boss for missing the flight to Milwaukee. He had called into the office from Memphis, feigning illness. He returned to his home city on a direct flight.

The following week Josh avoided flying by hanging around the office. This was quite unusual for a field salesperson, but Josh found a myriad of flimsy excuses—market research, sales reports that had to be updated, etc. His boss gave him a skeptical, impatient expression whenever they passed in the halls at the office. “You’re a sales guy, Josh. You should be out beating the bushes. Get your ass on a plane.”

And so Josh ended up on a plane again, or at least in an airport, waiting for a plane. It was Monday morning at around 6:30 a.m. The airport was starting to hum with its business of sending road warriors to distant locales.

After clearing security, Josh grabbed a cup of coffee at a kiosk. Then he found a seat in an isolated row of three. He sat in the middle seat and placed one of his bags in the seat on each side. Today he did not want to be joined by any strangers. Strangers in airports had been nothing but trouble lately.

Josh noticed a punk kid with wraparound sunglasses eating a breakfast sandwich at the airport McDonald’s, across the concourse from where he sat. The young tough stood out because hoodlum attire was unusual in an airport, where business dress prevailed.

Josh could not see his eyes: they were obscured behind the reflecting surface of his sunglasses. He was a burly type, and he apparently worked out: his muscles seemed ready to burst from the sleeves of his black motorcycle jacket.

The punk kid took another bite of his sandwich.

Only it wasn’t a breakfast sandwich. It was a human hand—by the looks of it, freshly severed from someone’s arm.

Josh choked on a mouthful of lukewarm coffee.

Just then the kid glanced up and leered at Josh. He pulled his sunglasses down onto the bridge of his nose, so Josh could see that there were only empty sockets where his eyes should be. He had no eyes to see Josh with, but he was looking right at Josh anyway. He pushed the sunglasses back into place and laughed. Josh heard the laughter despite the intervening distance and the loud buzz of activity all around him. The laughter seemed to be just a few inches from his ears, as if the hoodlum were capable of throwing his voice.

Then he dropped his grisly meal on the table where he sat and stood up.

(“There are good ones in here as well as bad ones.”)

(“Stay out of here if you can.”)

Josh wasn’t about to wait for this ghost—definitely one of the bad ones—to approach him. Forgetting all about his carry-on bag and laptop, Josh bolted from his seat, back toward the concourse exit. He was barely aware of all the people who were staring at him. He was sucking air in such short, rapid breaths that he feared he would pass out at any moment.

Josh had no idea if the hoodlum was following him. He did not dare to turn around as he ran.

After he had put enough distance between himself and the McDonalds, Josh ducked into a bookstore. It was a miniature airport version of Barnes & Noble.

The inside of the bookstore was a maze of ten-feet-high shelves. When he stopped, Josh found himself in the business section. He noticed the spine of a book about Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates, another one apparently written by Alan Greenspan.

He was sharing the space between the shelves with a woman who had long blond hair. Her back was to him. She was standing and reading, apparently absorbed in a book.

“My God,” Josh said, trying to catch his breath. “Oh my God.”

“Oh, God has nothing to do with it,” the woman said.

Josh was still shaking. He was in no mood to listen to the philosophical ramblings of a stranger. At first he considered ignoring her. But then he thought: no, she would continue talking until he acknowledged her.

“Ma’am, please, I’m having what you might call a very bad day.”

The woman turned around to face Josh. The better part of her skin was torn or rotted away. Josh stared into a horrible rictus of a smile that was mostly bare skull. But the teeth had grown long, now no longer human. Yellow incisors lined the thing’s upper and lower jaws.

“In here,” she laughed with a sound like pieces of rusty metal scraping together. “In here there is no God.”

And then Josh screamed, without the slightest thought of how he sounded or who heard. As he fled from the bookstore the cashier and two customers stared at him in agape silence. Josh knew that they could not see the half-woman, half-demon in the aisle behind him. They no doubt thought that he was crazy.

And Josh did not care.

* * *

Nick Dreyer and his partner Lonnie Mullins struggled to buckle the full body restraints on the screaming man. The guy was raving about incomprehensible things—people coming to get him and something about a woman with long teeth and rotting skin.

Nick was new to airport security. Aside from the statistically unlikely event of a terrorist or a drug smuggling bust, he had expected airport security to be an easy gig. After all, most people who could afford to fly were mild-mannered.

But this guy was raving like a lunatic. Nick and Lonnie had been summoned to remove him from Concourse A. He had been running through the concourse, swinging his arms wildly in all directions, as if warding off invisible attackers.

And he still refused to shut up. As the now restrained prisoner continued to buck in his chair, he stared out the open doorway of the airport security office.

Josh Gardner’s eyes seemed to be fixed on something that was just outside the office. Nick and Lonnie looked in the direction Josh was looking, but they could see nothing.

“What’s he lookin’ at?” Nick asked.

“No freakin’ clue. Seems to be hallucinating,” Lonnie speculated. “Anyway, shut the freaking door. This is enough of a show as it is.”

As Nick shut the door, Josh screamed at him, half angry, half pleading.

“It’s already in here! You can’t see it; but you already let it in!”

“Gag him,” Lonnie said. “I’ve had enough of this.”

“With what?”

“There’s a loading strap in my upper righthand desk drawer that should do the trick.”

“Won’t we get sued? Can we do that?”

Lonnie sighed. “I guess not. But just look at the guy, will you? Listen to him. He’s hysterical. I wish he would shut up.”

“He doesn’t seem quite ready to shut up yet, does he?”

“Hey, don’t let that chair tip over. Then we will get sued.”

* * *

Alan Sikorsky found himself thinking about lunch as he reviewed a printout of Josh Gardner’s resume. The clock in his office edged toward 11:35 a.m.

Josh’s resume indicated that he was a real hotshot: three years in field sales at EntroSoft. Made quota every quarter. Three times in the EntroSoft “Winner’s Circle”—an honorary designation for salespersons who have the highest results in any given quarter.

But Josh Gardner didn’t look the part of a star salesman. He lacked the in-your-face gregariousness that was such a crucial aspect of the sales personality.

In fact, he seemed to be a little on the timid side.

“So you resigned from EntroSoft last month rather suddenly.”

“Yes.”

“Any reason in particular?”

“Health issues. Plane sickness, actually. It turns out that I can’t fly anymore.”

“I see. Well, this position here at Pinnacle Star Communications would be inside sales only. You’ll spend most of your day cold calling, but there’s no travel involved. Do you think you can sell over the phone?”

Josh brightened. A new vista of opportunity seemed to be opening up before him. “I’m sure of it, Mr. Sikorsky. Sales is in my blood.”

Sikorsky uncapped a yellow highlighter and drew a circle at the top of Josh’s resume. This was the way he marked the paperwork of people he wanted to hire.

“Well, Mr. Gardner, we’ll have to run the routine criminal background check on you before we make this official. Oh, and you’ll have to pass our drug screening, too. But I can tell you off the record that your chances look pretty good. We’ve been wanting to poach some Entrosoft sales talent for quite some time.”

Josh sighed. “Thank you, Mr. Sikorsky. I won’t let you down.”

“Yes. A shame about your—stomach problems, though. You must have been pulling down quite a salary at Entrosoft, flying all over the country for them.”

“Yes, but well…my stomach problems.”

“To tell you the truth, I used to travel every week myself. However, I finally had to give it up.”

“So you didn’t care for flying either?”

“No. And this may sound strange to you—but I particularly disliked waiting in airports. On some trips I’d have layovers of three or four hours.”

“I know,” Josh said. “I know. I’ve been there.”

“All that time sitting around. And all those people. Some of them…well—”

Sikorsky knew he was rambling, saying more than he really should. But he didn’t believe that Josh Gardner had given up a six-figure sales job at Entrosoft because of a little flight sickness. And he thought that he recognized the lingering symptoms of serious trauma in Josh’s expressions and manner. It was a set of symptoms that he knew intimately.

“You meet all sorts in an airport,” Sikorsky went on. “All sorts of well…lost souls. Do you know what I mean?”

The younger man nodded; and Sikorsky noticed that Gardner’s arms had broken out in gooseflesh.

“You do seem to know what I mean, Josh.”

“I—” Josh Gardner paused, a half-formed utterance stuck in his partially opened mouth.

Sikorsky held up his hand. “Later, Mr. Gardner.” Sikorsky suddenly felt the skin on his own arms go prickly. “If things work out and you join us here at Pinnacle Star, perhaps we can swap some war stories over coffee sometime. I’ve flown all over the country; all over the world, in fact. And I’ve got some real doozies that I can tell you.”

THE END